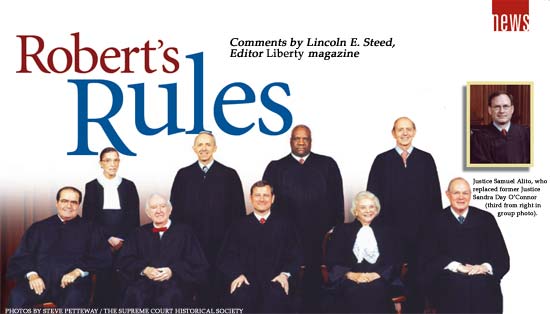

Robert’s Rules

Lincoln E. Steed March/April 2006

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

There is a certain irony in the fact that most of the Rehnquist Court were Republican/conservative appointees. But at the same time it somewhat vindicates the intent of the framers of the Constitution that the Court, by having tenure, be above party loyalty. However, if you listen carefully to the cry of partisans—and in particular the Religious Right—they are more and more calling for the appointment of ideologues who will push agenda over law. This is problematic to all liberty.

Roberts at his confirmation seemed a poster boy for middle-American values. And he may prove to be, without threatening religious freedom issues. But listening carefully to his spare comments and reading his paper trail show a clear identification with a judicial/constitutional worldview that is problematic.

In testimony he hedged on whether there is a general constitutional guarantee of privacy. Of course, that signals he may not favor Roe v. Wade and abortion. While we can rightly join religious activists in decrying the whole abortion model, it did arise from well-thought-out models of the rights of the individual versus the state. Roberts seems to share a growing conservative view that rethinks individual rights. The implications for religious freedom and divergent religious thought are troubling.

Roberts is on record as being uncomfortable with a strict separationist view of the First Amendment. This will further enable things such as the faith-based initiative of the Bush administration—a historic move across the line of separation and one that should properly have been declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

It has been remarked that some of Roberts' noncomments in hearings are eerily similar to those of Clarence Thomas, who is radically conservative in the mold of Antonin Scalia, who opined not long ago that Sunday blue laws are not unconstitutional.

In reality the issue is not quite one of conservative versus liberal in the old sense. The Religious Right has introduced a moral agenda to conservatism that creates a split between the old conservative models of fiscal policy and government restraint and a new reactionary one that has an agenda to reclaim America to a specific historic model of behavior and faith. This new movement has also successfully demonized liberalism by casting it as the mind-set of immorality.

It is worth noting that Scalia best enunciates the new conservative judicial model when he speaks of original intent and textual accuracy. He and others are quite open about this, and it fuels the charge against liberals of legislating from the bench. For Scalia the document means what it says—no more, no less. Of course, the Constitution is a very spare document by design, so many of the modern models are a poor fit taken literally. In those cases Scalia and many of the new conservatives look to original intent. This involves more than a little projecting of their own views into the minds of 200 years ago, and not a little endorsing of views of freedom and religion that we find abhorrent today. Look to a court dominated by such "conservatives" to encourage state involvement in religion, to restrict religious expression that is out of the mainstream, to uphold the prerogatives of business and property (read less rights of divergent religious expression in the workplace), to further empower the executive power, and in general to roll back freedom issues of the past 50 years.

However, if the Court is subject to the influence of the current line of judicial liberalism, we may equally fear for religious freedom.

Justice Scalia regularly demeans those of his fellow justices who hold to a view of a "living" or "evolving" Constitution, whereby they adopt the principles and ideals of the document to today's realities. Justice Stephen Breyer just admitted to this charge in a recently released book outlining his philosophy. It is well thought out and responsible—but in a crisis this mind-set also could subvert religious freedom if the nation seemed to demand it.

In the chaos of the election of 2000 the Supreme Court effectively conferred the election to George Bush because, as Scalia famously put it, there was a good chance that he would lose if they did not act. They did have the right to make a determination—but it ignored the fact that there were other, constitutionally mandated, procedures to follow in an electoral impasse. Here even a conservative-dominated court somewhat responded to political clamor rather than closely adhering to legal proscription. Breyer overtly says that justices should rule based on evolving democratic norms.

For too many, a less-separated church and state is, if not a norm, an agenda item. I fear that both the presently conservative court or a court influenced by an evolving view of the Constitution could as easily restrict true religion.

___________________________

Comments by Lincoln E. Steed, Editor Liberty magazine

___________________________

Article Author: Lincoln E. Steed

Lincoln E. Steed is the editor of Liberty magazine, a 200,000 circulation religious liberty journal which is distributed to political leaders, judiciary, lawyers and other thought leaders in North America. He is additionally the host of the weekly 3ABN television show "The Liberty Insider," and the radio program "Lifequest Liberty."