Section 295-C

May/June 2011

On one level it sounds so modern, so Western, so civilized: "Section 295-C" of the "Pakistani Criminal Code." On the other hand, as interpreted in the courts, it sounds like something from the Middle Ages, because, if violated, "Section 295-C" can lead to a death sentence.

Death sentence? That's not Middle Ages. Even in America, some states still kill people on death row. One slight difference, though. In America, a death sentence—when it is carried out (which is less and less frequently)—is generally for first-degree murder; in this case, in Pakistan, under "Section 295-C," it's for, of all things, blasphemy.

Talk about the Middle Ages! This, though, isn't the Middle Ages. It's now—the twenty-first century.

The Charge

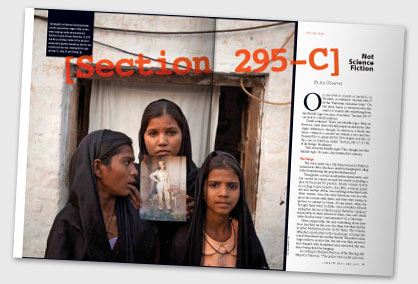

The story centers on a Christian woman in Pakistan named Asia Bibi, who faces death by hanging for, allegedly, blaspheming the prophet Muhammad.

Though her case has made international news, and has caused an outcry around the world, including a plea by the pope for pardon, details remain spotty. According to news reports, Asia Bibi, a woman in her 40s and mother of five, was working in the field with other women. Asia, the only Christian, was in a religious discussion with them, and they were trying to get her to convert to Islam. At one point, when she brought them water to drink, some coworkers refused, saying that she was a Christian and, therefore, "unclean." Apparently, in their version of Islam, you can't drink water that has been "contaminated" by a Christian.

Next, supposedly, she said something about how Jesus had died on the cross for them but what did the prophet Muhammad ever do for them. The women, offended, reported her to the local imam. At one point a mob threatened her and her family. The police came, supposedly to protect her, but she was then arrested and charged with blasphemy and convicted, the sentence being death by hanging.

According to Shahzad Kamran, of the Sharing Life Ministry Pakistan: "The police were under pressure from this Muslim mob, including clerics, asking for Asia to be killed because she had spoken ill of the prophet Muhammad. So after the police saved her life, they then registered a blasphemy case against her."

Section 295-C has its roots in nineteenth-century colonial legislation that was simply there to protect places of worship. It was under rule of General Mohammad Zia ul-Haq in the 1980s, as part of his effort to Islamize the state, that it became so draconian. Under the law, anyone who speaks ill of Islam and the prophet Muhammad faces the death penalty. Activists, though, argue that its "vague" terminology has led to its misuse. Section 295-C reads, in part, that "derogatory remarks, etc., in respect of the Holy Prophet," "either spoken or written or by visible representation, or by any imputation, innuendo, or insinuation, directly or indirectly, . . . shall be punished with death, or imprisonment for life, and shall also be liable to fine."

Although no one has been executed under Pakistan's blasphemy laws, as many as 10 people have been murdered while on trial. Many fear this will be the fate of Asia. In fact, if she were released, she and her family would have to flee; otherwise, her fate would be sealed. Some worry that even now, in prison and under protection, Asia Bibi is not safe. Indeed, earlier in December, a pro-Taliban Muslim cleric offered a $5,800 reward to anyone who killed her. Another cleric volunteered that he was not worried if she was freed or not, because any good Muslim would be happy to kill her.

Supporters of various religious parties wave party flags while shouting slogans during a rally in Lahore, December 24, 2010, demanding punlishment for Asia Bibi.

Supporters of various religious parties wave party flags while shouting slogans during a rally in Lahore, December 24, 2010, demanding punlishment for Asia Bibi.

Religious Assassination

Not all Pakistanis agree with what's happening. Many are appalled. In fact, the case of Asia Bibi has revealed a deep rift in this already greatly troubled land (one, we might add, armed to the teeth with nuclear weapons) between the Muslim extremists and others of the Muslim faith. Though Pakistan's leaders want to keep up a good relationship with the West, especially the United States, they also have to placate the extremist wing, and thus might not be inclined to antagonize them by showing her leniency.

Indeed, the degree of intensity was revealed with the assassination of Salman Taseer, the governor of the most populous state in Pakistan, Punjab. Taseer strongly opposed Section 295-C and sought a presidential pardon for Asia Bibi. For his trouble he was gunned down by one of his own bodyguards because he had visited her in prison and stated that the law was unjust. Though some condemned the killer, others, the extremists, view him as a national hero.

Because of the outcry over Asia Bibi and her death sentence, there has been some talk about modifying the law. The result was massive civil disobedience, including a strike, where protestors said that the law would be changed "over their dead bodies." Public transport came to a standstill in the city of Karachi, where demonstrators blocked traffic in protest. At this point, most of that talk about changing the law has stopped because the government fears such a change would play into the hands of the extremists.

"I state with full responsibility that the government has no intention to repeal the blasphemy law," Religious Affairs minister Syed Khurshid Shah said.

International Outcry

Asia Bibi's case has not gone unnoticed around the world. Numerous international human rights organizations have taken up her cause (in fact, during her trial, she had 10 lawyers, something unheard of in Pakistan for an impoverished farm worker).

Even Pope Benedict got involved, issuing the following plea: "Over these days the international community is, with great concern, following the situation of Christians in Pakistan, who are often victims of violence or discrimination. In particular, I today express my spiritual closeness to Ms. Asia Bibi and her family while asking that, as soon as possible, she may be restored to complete freedom. . . . I also pray for people who find themselves in similar situations, that their human dignity and fundamental rights may be fully respected."

However well-intentioned Benedict's words, it might only add to the fervor against her in Pakistan, being seen as more "proof" of Christian plots against Islam.

Maulana Yousef Qureshi (R) addresses a rally in Peshawar December 3, 2010. The hardline, pro-Taliban Pakistani Muslim cleric offered a reward for anyone who kills Asia Bibi. Qureshi, the iman of a major mosque in the northwestern city of Peshawar, offered a US$5,800 reward and warned the government against any move to abolish or change the blashphemy law.

Maulana Yousef Qureshi (R) addresses a rally in Peshawar December 3, 2010. The hardline, pro-Taliban Pakistani Muslim cleric offered a reward for anyone who kills Asia Bibi. Qureshi, the iman of a major mosque in the northwestern city of Peshawar, offered a US$5,800 reward and warned the government against any move to abolish or change the blashphemy law.

Religious Persecution in Pakistan

Asia Bibi's case, as well as the assassination of Salman Taseer, is only part of a larger picture of religious strike and intolerance in Pakistan. For starters, though blasphemy convictions are common, most convictions are thrown out on appeal, even if those accused are often killed by mobs.

One of the worst attacks on Christians, who make up only 4 percent of the Pakistani population, occurred in a town in the province of Punjab, where a mob of more than 1,000 Muslims burned 14 Christians to death. The attacks were triggered by reports of the desecration of the Koran. To this day, the details are unknown.

Last July two Christian brothers, accused of writing a blasphemous letter against Muhammad, were gunned down outside a courtroom. Hence a conviction or even an accusation under this law is often a death sentence, activists say.

At this point, no one knows what will be the fate of Asai Bibi and her family. Even if released, she will have to flee, that's for sure. Whatever the ultimate outcome, Section 295-C of the Pakistani Penal Code reveals the depth of the rift between Western values of religious freedom and those of extremist Islam, a rift not likely to be closed anytime soon.