Speak Freely, Without Fear

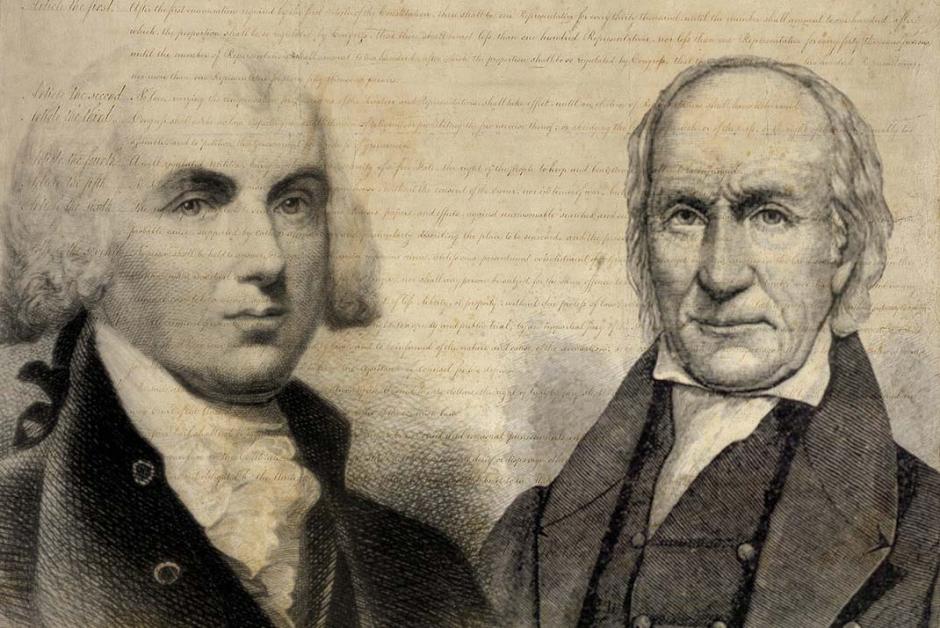

Reed Richardi November/December 2020In early America dissenting Baptists played a key role in the fight for religious liberty and the disestablishment of state churches. But while many Baptists fought for liberty for themselves, only a few fought for religious liberty for everyone. John Leland was one of those few. Leland was not only the most prominent Baptist but also the most prominent religious figure of the founding era to champion universal religious freedom. He was an energetic and popular preacher, witty writer, friend to presidents, and chauffer of a “Mammoth Cheese,” who radically advocated for freedom for Protestants, Catholics, Jews, Pagans, Muslims, Atheists, and slaves. The legacy of John Leland includes his influence on James Madison and the Bill of Rights, his delivery of a letter and a 1,235-pound wheel of cheese to Thomas Jefferson (and Jefferson’s famous reply to the Danbury Baptists), and finally his fight against Sabbath legislation in early-nineteenth-century America.

Born and raised in Grafton Massachusetts, John Leland was baptized in 1774 at the age of 20 after experiencing a religious awakening. Just a few weeks later Leland attended Sunday services at a church where there was no preacher and reluctantly stood up to preach. The sermon began shakily, but he improved as it went on. Afterward the congregation encouraged the trembling young preacher, and that afternoon Leland surrendered himself to the work of the ministry, “without any condition, evasion, or mental reservation.” Leland immediately began preaching in nearby towns and worked tirelessly for the rest of his life to save souls and preach the gospel. Over the course of the next 67 years Leland would (according to his own records) preach more than 8,000 sermons, baptize 1,524 people, and travel enough in his labors to circumnavigate the globe three times.

After spreading the Baptist message in Virginia as an itinerant preacher, Leland settled down in 1778 with his new wife, Sally Devine, in Orange County, Virginia. For the next 13 years they would reside only 10 miles from James Madison’s Montpelier and 30 miles from Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Leland was very active in Virginia, often preaching 12 or 14 times a week, founding several churches and serving at a half dozen others in surrounding counties. The respected early Baptist historian Robert Semple wrote that “Mr. Leland, as a preacher, was probably the most popular of any who ever resided in [Virginia].”

In the years leading up to the Revolution, to the dismay of the established Anglican Church, the Baptist revivalists met with tremendous success in Virginia. But that success came at a price. Baptist preachers were beaten, harassed by mobs, and arrested, not only as disturbers of the peace but also because they refused to apply to authorities for licenses to preach (the Baptist preachers, including Leland, thought it idolatry to apply to a civil power for the right to preach God’s Word). The evangelical dissenters turned to political measures to protect their freedoms and found champions in such secular intellectuals as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. By the time Leland began his ministry in Virginia there was already precedence of political activism among the increasingly influential Baptists.

Taking advantage of his popularity as a preacher, Leland used writing to advocate for religious freedom. He wrote about religion and religious liberty with a forceful style and sharp wit. Two passages from Leland’s writing while in Virginia will serve as representative of the whole. In The Virginia Chronicle, published in 1790, Leland wrote that “the notion of a Christian commonwealth should be exploded forever. . . . Government should protect every man in thinking and speaking freely, and see that one does not abuse another. The liberty I contend for is more than toleration. The very idea of toleration is despicable; it supposes that some have a preeminence above the rest, to grant indulgence, whereas all should be equally free, Jews, Turks, Pagans and Christians.

Leland’s treatise The Rights of Conscience Inalienable, published on January 1, 1791 (the year he moved back to Massachusetts), was his most famous and influential work. The following is an excerpt.

“Is conformity of sentiments in matters of religion essential to the happiness of civil government? Not at all. Government has no more to do with the religious opinions of men than it has with the principles of mathematics. Let every man speak freely without fear—maintain the principles that he believes—worship according to his own faith, either one God, three Gods, no God, or twenty Gods; and let government protect him in so doing, i.e., see that he meets with no personal abuse or loss of property for his religious opinions. Instead of discouraging him with proscriptions, fines, confiscation or death, let him be encouraged, as a free man, to bring forth his arguments and maintain his points with all boldness; then if his doctrine is false it will be confuted, and if it is true (though ever so novel) let others credit it. . . . Truth disdains the aid of law for its defense—it will stand upon its own merits. . . . It is error, and error alone, that needs human support.”

Leland himself played an influential role in the opposition to Patrick Henry’s general assessment bill in 1784, and in the disestablishment of the state church in Virginia (and later in Massachusetts and Connecticut). But perhaps his greatest contribution to religious liberty was his role in the ratification of the federal Constitution by Virginia and Madison’s guarantee of a Bill of Rights.

The federal Constitution, drafted by James Madison, was voted by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. But with strong opposition from the Anti-Federalists, the ratification of the Constitution by the states was no sure thing. One of the principle objections by the Anti-Federalists was that it did not include a Bill of Rights. Madison himself supported the ideals of a Bill of Rights but did not believe their inclusion in the Constitution was necessary (instead he believed that individual rights were implicit in the Constitution, all powers not expressly given to the federal government being retained by the people). Virginia, the largest, most populous, and perhaps most important state politically, was also home to a majority of the most prominent and influential Anti-Federalists (George Mason, James Monroe, Richard Henry Lee, and Patrick Henry). At the time it was widely believed that ratification in Virginia was absolutely essential for the Constitution to succeed. Almost immediately after the convention in Philadelphia, Baptists in Virginia and other states began opposing the Constitution, not because of what it stated, but because of what it did not state. On March 7, 1788, the Virginia Baptist General Committee, led by John Leland, met to discuss the proposed Constitution. They voted a resolution which in part stated that “we the Virginia Baptist General Committee unanimously hold that the new federal constitution, proposed to the States for their ratification, does not make sufficient provision for the secure enjoyment of religious liberty; and therefore it should be amended to make such a provision.”

James Madison was in New York attending Congress and writing the Federalist Papers when he learned through numerous letters of the strength of the Anti-Federalists in Virginia as well as the Baptist opposition to ratification. On February 17, 1788, Madison received a letter warning him that “several of those who have much weight with the people are opposed” to ratification. John Leland was one of three individuals mentioned by name. Madison decided to return to Virginia to run as a candidate for the ratification convention. While passing through Fredericksburg on his return trip, Madison received a letter from Captain Joseph Spencer that described the Baptist opposition to ratification and urged Madison to “spend a few hours” talking with John Leland on his way home to Montpelier. Enclosed in the letter was a copy of 10 objections to the Constitution written by John Leland. Leland’s principle objections were that the Constitution contained no Bill of Rights and did not adequately secure religious freedom but left it in the hands of the president and Congress.

Undoubtably Madison took Spencer’s advice, and went to see Leland. The two reportedly met on March 23, 1788 (the day before the election), at Gum Springs, near Leland’s home. In the meeting Madison is said to have pledged his support for a Bill of Rights, and in turn Leland pledged his support for Madison and the ratification of the Constitution. Leland and the Baptists did indeed support Madison, who was elected the next day to the Virginia Ratifying Convention.

At the Virginia Ratifying Convention in Richmond, Patrick Henry and George Mason had the oratorical advantage and used it to strongly oppose ratification. But Madison, the Constitution’s author, argued influentially for a republican government established by a constitution in which mutually accountable branches of government were grounded in the people without hereditary office. The vote was taken on June 25, 1788, and by a margin of 89 to 79, the Constitution was ratified by Virginia. Included in the vote was a recommendation for the addition of a Bill of Rights. New York soon followed Virginia’s example and voted to ratify. The tide had turned: the Constitution and the Federalists had carried the day.

On May 4, 1789, just four days after Washington’s inauguration, Madison declared his intention to propose amendments to the Constitution. On June 9, 1789, in an address to Congress, Madison formally proposed the amendments. In the outline of his notes for the address Madison wrote “Bill of Rights—useful—not essential.” Though Madison did not see the Bill of Rights as essential, he knew that others did. In his address he said: “It cannot be a secret to the gentlemen in this house that . . . there is a great number of our constituents who are dissatisfied with [the Constitution]. . . . There is a great body of the people falling under this description, who at present feel much inclined to join their support to the cause of federalism, if they were satisfied in this one point.”

Madison clearly had his constituents like John Leland in mind. He went on to argue that the amendments would prove that the trust in him and the other Federalists was not misplaced, and that the Federalists were indeed friends to liberty. Madison not only proposed the amendments to Congress but championed them throughout the legislative process. Leland and his fellow Baptists had their way, when, on December 15, 1791, the Bill of Rights came into effect as constitutional amendments, and liberty was made more secure. Historian Gordon Wood writes that “there is no question that it was Madison’s personal prestige and his dogged persistence that saw the amendments through the Congress. There might have been a federal Constitution without Madison, but certainly no Bill of Rights.” Without Madison there might not have been a Bill of Rights, and without Leland, Madison may never have been their champion. May we not forget the impact that religious and religious liberty-minded people like John Leland had in shaping our nation during that crucial time.

Article Author: Reed Richardi

Reed Richardi writes from New Market, Virginia.