Speaking as a Brother

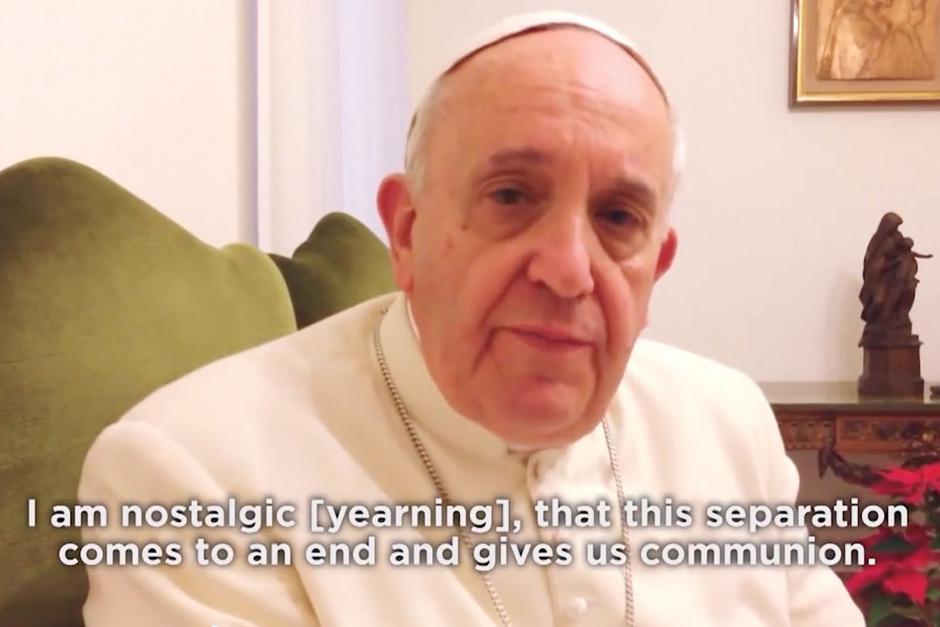

Clifford R. Goldstein November/December 2014It was, on the face of it, remarkable. Arguably one of the most influential leaders in the world, unarguably the most influential religious leader in the world, Pope Francis appeared in a short video as a humble suppliant, a simple brother speaking obsequiously, even apologetically, to Protestants in the United States. From his opening words, “Dear brothers and sisters, excuse me,” to some of his last, “I ask you to bless me,” the pope came across with an endearing, even disarming, earnestness that one might associate with a beggar on the street, and not with the bishop of Rome. Everything in the video—from the simple room in which it was shot, to Francis’ demeanor, to his words themselves—exuded a loving and self-effacing humility that gave his plea for Christian unity a power manifestly lacking in any official Vatican decree.

This remarkable seven-minute video was played before a gathering of Pentecostal preachers at the Kenneth Copeland Ministries annual ministers conference, held January 21, 2014, in Fort Worth, Texas.

Recent political changes in America have caused some to say, “It’s not your father’s country.” An event like this—a pope humbly addressing, and being enthusiastically received by, a conservative Protestant church in the United States, all on the subject of Christian unity—could justifiably make one say, “It’s not your father’s church,” either.

The pope’s video was preceded by a live homily from Bishop Tony Palmer, a member of a breakaway Anglican community, the Communion of Evangelical Episcopal Churches, and founder of the Ark Community, which calls itself “an international community of Christians, coming together to form intimate relationships based upon a common spiritual pilgrimage.” Palmer also worked a few years for Kenneth Copeland Ministries.

A friend of both Francis and Copeland, Bishop Palmer shot the video of the pope on his iPhone and then brought it to the conference, where it was played, but not before Palmer declared to these Pentecostal preachers that no reason for the Catholic-Protestant chasm still existed. Arguing that the 1999 document “The Joint Declaration of the Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation on the Doctrine of Justification” showed that Catholics and Protestants had bridged the main theological divide between them, i.e., the question of salvation by faith alone, Palmer called for unity between Protestants and Catholics.

“Brothers and sisters,” Palmer declared, “Luther’s protest is over. Is yours?” Then, after he read from John 17 Jesus’ prayer for unity, the video was presented.

With the camera right up to his face, the pope began in heavily accented English, speaking very slowly. “But I am not speaking English. But I will speak no Italian, no English, but ‘heartfully’ [sic].” Then, switching to Italian, he continued: “It’s a language more simple and more authentic, and this language of the heart has a special language and grammar.”

With this introduction Francis immediately set a tone, basically saying without saying it that this isn’t a papal encyclical, a Vatican decree, but rather a humble brother in the faith talking from his heart to others in the faith—not a typical approach for a pope. It’s a radical change, for instance, from Boniface VIII’s papal bull Unam Sanctum (1302), in which he declared that “it is absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff.”

Francis next talked about how glad he was to greet this meeting, and he made reference to the division between Protestants and Catholics. “We are kind of, permit me to say, separated.”

“Permit me to say.” Again, he’s speaking in the language of a humble suppliant, not of the “vicar of Christ.”

Francis then gets into the heart of his message: “Separated,” he said, “because, it’s sin that has separated us, all our sins. The misunderstandings throughout history. It has been a long road of sin that we all shared in. Who is to blame? We all share the blame. We have all sinned. There is only one blameless, the Lord. I am [yearning] that this separation comes to an end and gives us communion. I am [yearning] of that embrace that the Holy Scripture speaks of when Joseph’s brothers began to starve from hunger—they went to Egypt to buy, so that they could eat.”

Here’s where the subterfuge begins. It’s “our sins” that have caused the separation. Numerous times he talked about everyone’s sins, meaning obviously the sins of both Protestants and Catholics. Of course, the Protestants were sinners, and the early Reformers were not always angels, either. But the Reformation was hardly the result of “misunderstandings throughout history.” Rather, it was a biblically based revolt against an ecclesiastical system that, at its core, had corrupted the gospel of Christ and replaced it with a human-made hierarchical system that all but usurped the work of Jesus Christ in behalf of humanity.

The pope’s use of the story of Joseph and his brothers was shallow enough to be vague, but the point wasn’t lost. Joseph’s brothers (the Protestants) were starving; they needed something that they didn’t have, so they had to go to Egypt, back to their brother Joseph (the Roman Catholic Church), in order to get it.

With the Joseph story, however, Francis might have revealed more of his true sentiments than intended. Joseph’s brothers were mostly evil, treacherous men who, out of jealousy and hatred, wanted to kill Joseph and throw his corpse into a hole (Genesis 37:20). Perhaps having twinges of guilt, they sold him into slavery instead. They then dipped his clothes in animal blood, which they took back to their father.

Thus, in Pope Francis’ homily, the treachery of the brothers (the Protest-ants) caused the separation in the first place, a slight deviation from his earlier words about everyone being at fault. Then, only out of desperation for food did Joseph’s brothers go down to Egypt (an interesting analogy, because in the Bible “Egypt” is a symbol of sin and rebellion against God); and only then did they return to their long-lost brother, Joseph (the Roman Catholic Church), who—though justified in rejecting or even punishing these men—embraced them with tears instead, the “tears of love.”

However powerful a story of grace, forgiveness, and reconciliation, the account of Joseph and his brothers hardly serves as an honest metaphor for the Protestant revolt against Rome. A biblical story that more accurately depicts the principles involved with the Reformation would be some of the scribes and Pharisees, uniting with the secular Roman authorities, persecuting the early followers of Christ and forcing them to flee for their lives.

Pope Francis then followed with more humble words, such as: “I thank you profoundly for listening to me. I thank you profoundly for allowing me to speak the language of the heart. . . . I need your prayers. . . . From brother to brother, I embrace you. Thank you.”

Apart from the manner in which the pope spoke, and the way the message was delivered (by iPhone video?), Francis said nothing new, at least from the Catholic side of the divide, that hadn’t been said before, such as in John Paul II’s encyclical Ut Unum Sint (That They May Be One). What was remarkable was American Protestant leader Kenneth Copeland’s response once the video was over. Coming to the pulpit, amid the clapping and cheers of the audience, which had risen to its feet, Copeland uttered, “Oh, Glory! Glory! Glory!” and then said, “Come on, the man asked us to pray for him.” He prayed for the pope, saying that he too wanted the “unity in the body of Christ” that Francis was asking for.

Copeland then asked Tony Palmer to the pulpit, and with the same iPhone Palmer had recorded the pope, he had Palmer record him a message back to Francis, thanking God for the pope and affirming Francis in his desire for unity. Then, in what were the most accurate and honest words spoken amid what many could justifiably argue was one deception after another, Copeland said, in reference to the calls for unity with Rome: “I mean, when we went into the ministry 47 years ago, this was impossible.”

And that’s because 47 years ago Protestants understood what Copeland and many others today seem to have missed, which is that on the crucial issue of the Reformation, how people are saved, Rome has not changed its position at all. It has not repudiated the teaching of the Council of Trent (1545-1563), where it overtly rejected the Protestant stand on salvation by faith alone.

“If anyone says that justifying grace is nothing else than confidence [faith] in divine mercy, which remits sin for Christ’s sake, or that this confidence [faith] alone justifies us, let him be anathema” (Councils and Decrees of the Council of Trent, Canon 12). “Anathema,” by the way, means “cursed.”

These views are in stark contrast to the Protestant position that, yes, faith alone “justifies us” and that, no, justification is not also “sanctification and the renewal of the inner man.” However much to the uninitiated these might seem like theological nitpicking, the difference on this topic gets to the heart of the foundational question in Scripture: “How should man be just with God?” (Job 9:2). This difference also contains the pivot upon which Western Christianity split in the sixteenth century, the pivot upon which the Protestant Reformation first started before exploding across Europe. Most of the other issues that separate Catholicism from Protestantism—purgatory, indulgences, penance, the Mass, and the priesthood—originate to one degree or another from the Roman teaching that justification includes a righteousness that is infused in the life of the believer. This, in direct opposition to the Protestant teaching that justification is the imputation, the crediting, of God’s righteousness to the believer, which makes that person fully justified and forgiven before God. And this status, which is all one needs for salvation, comes by faith alone, and nothing else.

Despite all the attempts in recent years to come to reconciliation on this topic, and despite the exceedingly disingenuous use of common terms such as grace, and faith and justification, such as appear in the document that Palmer had mentioned, “The Joint Declaration of the Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation on the Doctrine of Justification”—the difference in understanding here has led to two radically different concepts of salvation. There’s a crucial reason that in Kenneth Copeland’s church the members don’t celebrate the Mass, don’t pray to saints, don’t confess sins to priests, and don’t receive indulgences.

For example, a Vatican decree in 2012 (Urbis et Orbis) in regard to “the gift of Sacred Indulgences,” reads in part: “All individual members of the faithful who are truly repentant, have duly received the Sacrament of Penance and Holy Communion and who pray for the intentions of the Supreme Pontiff may receive the Plenary Indulgence in remission of the temporal punishment for their sins, imparted through God’s mercy and applicable in suffrage to the souls of the deceased.”

Of course, Rome has the right to promote indulgences. But only through the most cynical and manipulative twisting of language can indulgences, and many other teachings like it, be said to be in harmony with the Protestant understanding of what Jesus had accomplished for humanity at the cross. Thus, one has to wonder about all the excitement, and the utterances of “Glory!” Kenneth Copeland expressed over Pope Francis’ exhortation for unity.

Protest Over?

It’s hard to imagine any of the 265 popes who preceded him making the kind of humble appeal that Pope Francis did in this iPhone video. (Could one see John Paul II, or Benedict XVI, doing this?) Yet, however refreshing this pontiff’s approach, Rome hasn’t changed its position on salvation. It remains as entrenched now as when the Council of Trent cursed the Reformers and when Rome began a violent campaign of religious persecution against Protestants that lasted for centuries.

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.