The Bridge to Tomorrow

Rex D. Edwards March/April 2009

“Never does the human soul appear so strong and noble as when it forgoes revenge, and dares to forgive an injury.” —Edwin Hubbell Chapin

On Monday, March 29, 1948, the city of Jerusalem had on hand only a five-day supply of margarine, four days of macaroni, and ten days of dried meat. There was no fresh meat, fruit, or vegetables available in its markets. Any eggs that could be found sold for 20 cents apiece. The city, with its 100,000 Jews, was living off its slender reserves of canned and packaged food: sardines, macaroni, and dried beans. Convoys bringing relief had been wiped out. With the road up to Jerusalem cut, one sixth of the entire Jewish settlement in Palestine was isolated and menaced by starvation.

Rationing had been avoided as long as possible so as not to create a climate of insecurity in the city. Now it began with a vengeance. Adults were allowed, for example, 200 grams (about four slices) of bread a day. For children, a supplementary ration consisted of one egg and 50 grams of margarine a week.

Nor was food the only staple in short supply in the city. No kerosene had reached Jerusalem since February. Housewives had begun using DDT as cooking fuel. People learned how to improvise. Anyone with a patch of land or a window box tried to grow a few vegetables. For those who did not own even a flowerpot, a handful of erudite biologists at Hebrew University suggested hydroponics, a technique of growing vegetables in water without soil. Soaked cotton was recommended for nurturing seedlings.

Occasionally help came from the enemy. One night a Jewish householder heard a soft whistle coming from beyond the barbed wire ringing his home. Creeping to the sound in the dark, he found Salome, the elderly Arab woman who had been his maid for years. She passed him a few tomatoes through the wire, whispering, “I know you having nothing.”

As I read this account1 it struck me that this vignette of history was naming an aspect of that noblest—and rarest—of all human graces: magnanimity.

“No man ever saved anybody, or served any great cause, or left any enduring impress who was not willing to forget indignities, bear no grudges.”

The dictionary-makers define magnanimity as the quality of being “noble in mind; elevated in soul . . . ; rising above pettiness or meanness; generous in overlooking injury or insult.”2 C. P. Snow calls it “this major virtue, which at any level sweetens life, and at the highest glorifies it.” Of it, the late Harry Emerson Fosdick, the most famous Protestant preacher of a past era, wrote: “No man ever saved anybody, or served any great cause, or left any enduring impress who was not willing to forget indignities, bear no grudges . . . . The world’s saviors have all, in one way or another, loved their enemies and done them good.”

Magnanimity, applied to relations between nations and peoples, transforms hostility into helpfulness. Salome’s magnanimous act is quite astonishing considering a decision made on the afternoon of Saturday, November 29, 1947, in a cavernous gray building that had once housed an ice-skating rink, in Flushing Meadow, New York, when delegates of 56 of the 57 members of the General Assembly of the United Nations were called upon to decide the future of a sliver of land set on the eastern rim of the Mediterranean. Half the size of Denmark, harboring fewer people than the city of St. Louis, it had been the center of the universe for the cartographers of antiquity, the destination of all the roads of man when the world was young: Palestine.

Before the General Assembly was a proposal to cut the ancient territory into two separate states—one Arab, one Jewish. That proposal represented the collective wisdom of a United Nations special committee instructed to find some way of resolving 30 years of struggle between Jews and Arabs for the control of Palestine.

A mapmaker’s nightmare, it was categorized “at best, a possible compromise; at worst, an abomination.” It gave 57 percent of Palestine to the Jewish people despite the fact that two thirds of its population and more than half its land was Arab. The Arabs owned more land in the Jewish state than the Jews did, and before immigration that state would contain a majority of barely 1,000 Jews.

All these facts were known to Salome. She knew the partitioning of the land in which her people had been a majority for seven centuries was a monstrous injustice. Was her magnanimous response to the needs of a hungry Jew easy? When we feel sorely sinned against, our first impulse is to strike back, to exact the ancient world’s eye for an eye and tooth for a tooth. But the advent of Christianity brought a nobler goal: to “overcome evil with good” (Romans 12:21, KJV). “Love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who spitefully use you and persecute you” (Matthew 5:44, NKJV), Christ commanded.* To most of us such triumph over vindictiveness doesn’t come naturally. It’s a grace that must be developed, made habitual by practice. Jesus, asked how many times an enemy should be forgiven, replied: “Until seventy times seven” (Matthew 18:22, KJV).

Magnanimity does not condone wrongdoing, of course. Nor does it suggest that the wrongdoer should go scot-free, or “lessen the claim of just obligation.”3 He who forgives easily invites offense. But it does call for understanding the pressures that led to the transgression, plus a willingness to help the guilty one. “If you do not forgive,” said Jesus bluntly, “neither will your Father in heaven forgive your trespasses” (Mark 11:26, NKJV). In other words, those who refuse to forgive cast away their “own hope of pardon.” .”4 It is just. Why? Because we have been forgiven a debt that is beyond all paying. Our sin brought the death of God’s own Son, and if that is so, we must forgive others as God has forgiven us, or we can hope to find no mercy. The unforgiving unforgiven dies.

We are, in fact, called to not only forgive but to forget. While an injury is a part of our memory history, forgetting involves a deliberate act of the will, putting the injury out of our minds, refusing to dwell upon it. This takes some doing, but the person who says, “I can forgive, but I can never forget,” is saying, in the words of Henry Ward Beecher, “I cannot forgive.” Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, reminded once of a cruelty done her, replied serenely, “I distinctly remember forgetting that!”

General Wilfred Kitching, when international head of the Salvation Army, was fond of telling of the man who arose in one of his public meetings to testify: “God has not only forgiven my sins and cast them into the sea of His forgetfulness, but He has put up a notice, ‘Fishing Prohibited!’”

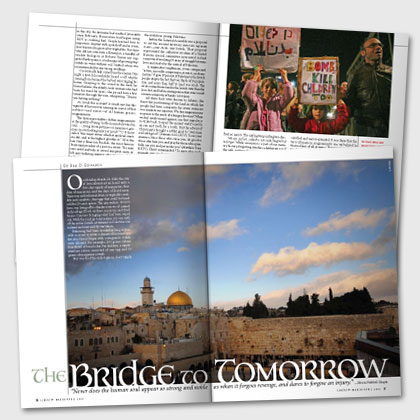

Two Israeli children hold banners during a protest in Tel Aviv against Israel’s offensive in Gaza January 2009. The left banner reads in English “Yes to peace.” REUTERS/Eliana Aponte

The Gospels make it plain that Jesus made magnanimity’s possession and practice the prime aim of those who would live the good life, the ultimate test of character. Consider His gentle treatment of the adulteress about to be stoned. Why would He not condemn her? Because He would be condemned for her. Innocence would not condemn, because innocence would suffer for the guilty. Justice would be saved, for He would pay the debt of her sins; mercy would be saved, for the merits of His death would apply to her soul. But He did not make light of her sin, for He assumed its burden. Forgiveness cost something, and the full price would be paid on the hill of the three crosses where justice would be satisfied and mercy extended. It was there that the very ultimate in magnanimity was verbalized in that noblest of all prayers: “Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do.”

Forgive whom? Forgive enemies? The soldier in the courtroom of Caiaphas who struck Him with a mailed fist? Pilate, the politician, who condemned a God to retain the friendship of Caesar? Herod who robed Wisdom in the garment of a fool? The soldiers who swung the King of kings on a tree between heaven and earth? Forgive them? And yes, the Jews who stole your land, dispossessed you, and bulldozed your house! And yes, the colleague who falsely accused you and assigned to another credit for your work! And yes, the professed Christian pastor who gives new meaning to the scandal of Christianity: when the righteous are ungodly. Why? In the words of the Duke of Buckingham,

“The truest joys they seldom prove

Who free from quarrels live:

‘Tis the most tender part of love

Each other to forgive.”

—John Sheffield

* Texts credited to NKJV are from the New King James Version. Copyright ©1979, 1980, 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

- Larry Collins and Dominique LaPierre, O Jerusalem! (New York: Pocket Books, 1972), p. 265.

- Webster’s New Twentieth Century Dictionary, unabridged, 2nd. ed. (1977), s.v. “magnanimous”; cf. “magnanimity.”

- Ellen G. White, Christ’s Object Lessons, p. 247.

- Ibid., p. 247.