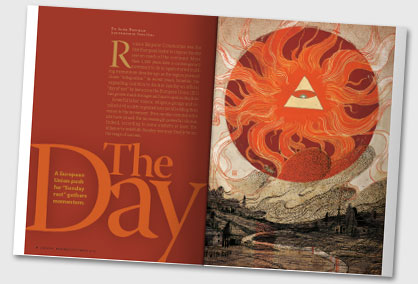

The Day

Alex Newman November/December 2012

Roman Emperor Constantine was the first European leader to impose Sunday rest on much of the continent. More than 1,500 years later a contemporary movement to do so again started building momentum decades ago as the region pursued closer “integration.” In recent years, however, the expanding coalition to declare Sunday an official “day of rest” by law across the European Union (EU) has grown much stronger and more open in its plans.

Powerful labor unions, religious groups and so-called civil society organizations are all adding their voices to the movement. Even secular-minded activists have joined the increasingly powerful chorus. Indeed, according to some analysts at least, the alliance to establish Sunday rest may finally be on the verge of success.

The series of events leading up to a potential Sunday “day of rest” began almost 20 years ago with the adoption of the original European Working Time Directive, an EU mandate ordering member governments to incorporate a set of minimum standards into national legislation. Since then the directive has been revised on several occasions. Thus far, however, efforts to formally enshrine Sunday rest across the bloc have not yet succeeded.

In early 2010 Member of the European Parliament (MEP) Martin Kastler, a prominent German Catholic, launched the first European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) to establish work-free Sundays at the EU level. “This initiative will strengthen direct democracy in the European Union,” he said in a press release at the time. “We want to use this opportunity to ensure a free Sunday.”

Kastler had not responded to repeated requests for comment by the time of publication of this article. However, after collecting nearly 20,000 signatures on the petition, his campaign seems to have largely fizzled out—probably in part because the ECI mechanism was not yet in force. Still, despite the setbacks, the work-free Sunday movement has hardly given up.

In more than a few countries and jurisdictions, the effort actually succeeded years or even decades ago. In Germany, for example, Sunday is protected in the national constitution. And with the widely expected upcoming revisions to European working rules—and the opportunity it offers to activists—the push to create an EU-wide day of rest on Sunday is quickly gathering steam again.

In June 2011 a budding umbrella coalition known as the European Sunday Alliance (ESA) was officially formed to advance the scheme. Composed primarily of national Sunday alliance groups, trade unions, nonprofit organizations, and religious denominations, the network orchestrated a massive “Day of Action” on March 4 of this year to promote the cause. Activists in more than a dozen countries, including Spain, Germany, France, Austria, and Belgium, participated in demonstrations calling for regional and national Sunday-work restrictions.

Of course, the Roman Catholic Church, the Orthodox churches, and many Lutheran churches especially are still at the forefront of the movement, though it has now garnered support from a broad coalition that includes secular groups. Together with the Catholic Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences of the European Community (COMECE), however, Pope Benedict XVI is among the key drivers behind the agenda.

“Tuesday, May 15, we celebrated the World Day of Families, established by the United Nations and dedicated this year to balance between two closely related issues: family and work,” explained Pope Benedict XVI in a recent speech at the Vatican. “This should not hinder the family, but rather support and unite it, helping it to be open to life and to enter into a relationship with society and with the church. I also hope that Sunday, the Lord’s Day and weekly celebration of His resurrection, will be a day of rest and an opportunity to strengthen family ties.”

However, whereas in the past the religious arguments were considered key selling points, today the effort is using justifications ranging from health and workers’ rights to the promotion of family time and social cohesion. Religion and the notion that most Christians worship on Sunday, meanwhile, has mostly been replaced with rhetoric-like “tradition” and “culture,” or even “cultural tradition.”

The Alliance and Its Mission

“The attempt of the alliance is not religious; it’s more about social cohesion,” says Johanna Touzel, the spokesperson and media contact for the ESA. The effort is based primarily on three pillars, she added: promoting workers’ health and well-being, ensuring adequate time for family life, and increasing social cohesion by allowing citizens to have a common day for sports, cultural endeavors, religious and spiritual fulfillment, volunteer work, and more.

According to Touzel and the Alliance, the liberalization of working hours to satisfy the “consumer society” is having harmful effects on families and health. In recent years there have even been published studies “proving that there is a link between the health of workers and Sunday work—scientific studies,” Touzel says. “And also it is proven that there is a need of cohesion in society that can only happen if you have a common day of rest.”

For centuries Sunday has traditionally been considered the day of rest in Europe; that is why it is the ideal day to enshrine in EU law, she opines. “What is important is to keep a common day of rest—it’s nothing against Muslims, against Seventh-day Adventists,” Touzel notes, adding that if most Europeans were to choose Saturday instead, that would be fine too.

The EU, of course, has no legal authority in matters of religion anyway, and the alliance likes it that way, she says, adding that religious affairs should remain in the realm of national governments in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity. “What is important to mention is that the main motivation is not religious, because we don’t want the European Union to take positions on religious grounds,” she says. “We simply say this question is first of all social—it’s about social cohesion and health.”

Rich people, Touzel notes, can go play golf on Sunday. But the poor often lack that freedom. “Let’s not forget that those people who work on Sunday, very often they don’t have a choice—they are again becoming the slaves that the Bible wanted to avoid by saying that on this day [the Sabbath—Exodus 20:8] there are no more slaves and masters. On that day everybody is free,” she continues. “We need to reintroduce solidarity and say that on that day everybody is on the same level.”

When asked about opponents, Touzel emphasizes that Sunday rest would only be included in the legislation with a key caveat: “in principle.” Essentially, that means it would not be a strict law with mandatory enforcement. “Of course there would be a lot of exceptions,” she adds, noting that the main targets would be big companies, such as grocery-store chains, that force small businesses to stay open on Sunday to avoid losing market share.

In addition, Sunday rest is just one component of the broader Working Time Directive. The alliance itself focuses on other issues, such as late working hours and labor conditions, too. But preserving a common day of rest, even just “in principle,” is key to society’s overall well-being, she says.

“The idea of the European Sunday Alliance is to gather all these ideas—all these successes also that we gained in the different national legislation—to show we have a common leader among the different member states,” Touzel says. “So let’s unite to ask—‘pressure’ is not a nice word—the European Community to respect, in its legislation, this day of rest.”

Next

A majority of political groups already support the Alliance, says Touzel, citing greens, conservatives, social democrats, and others. But there is still work to be done. “We are trying to mobilize all political parties, citizens, and different civil society organizations to show that there really is scientific proof that work on weekends—on Sundays—is harming the health of the people,” she says. “In the context of the current economic crisis, I think everybody realizes that society is more than just consumers. So I think our alliance comes just at the right moment.”

Right now, trade unions, employers, and other stakeholders are seeking an agreement on revisions to the European Working Time Directive. If one is reached, the EU’s institutions would presumably ratify it. However, securing a deal is expected to be difficult. The more likely outcome would be that the proposal would be taken up by the European Commission, analysts say.

By the end of the year, if the “social” parties don’t find an agreement, the draft directive will head back to the European Commission—essentially the executive branch of the EU. If approved, it would go to the European Parliament. The Council of Ministers representing member governments would also weigh in. From there, assuming the other bodies agree, the revisions could become official.

Even if Sunday rest does not succeed through the more traditional political routes, however, Touzel says the alliance may pursue an ECI—a relatively new concept that went into effect only this year. If supporters can gather at least 1 million signatures from nine member states, the EU would be forced to at least consider legislative action.

“This would be a second tool that we could use to pressure the European Commission,” Touzel explains. “It is a really heavy endeavor, but we will consider it if the other way doesn’t work.”

The Opposition

Despite the seemingly broad-based support for Sunday rest, there are opponents. Apparently the United Kingdom’s government has fought hard against many of the EU restrictions on working time—especially the 48-hour-per-week limit. It even managed to get exceptions to some mandates, though that has been under fire for some time.

Numerous retail employers are also said to be battling the effort because so much of their revenue comes from Sunday shoppers—many of whom enjoy being able to shop on Sunday, too. Libertarians who disagree with any mandates are opposed to the rules in principle, though their opposition has not been particularly loud thus far.

Of course, there are the religious groups as well. Jews and some Christians—most notably Seventh-day Adventists—observe the biblical Sabbath and worship on Saturday. Muslims, meanwhile, worship on Friday, and Islam has become a sizable and powerful minority throughout Europe in recent times.

“We have one element that is valid for all European citizens: freedom of practice of religion,” says Serge Cwajgenbaum, secretary general of the European Jewish Congress. “To have one European common day for all European citizens on a specific day would probably create more problems than it solves.”

According to Cwajgenbaum, who said Jews are largely satisfied with the status quo and would like to maintain it, selecting a specific day of rest for the whole EU could antagonize various groups and followers of religious faiths. “It would create more problems, and we have enough problems in Europe—enough tensions,” he adds. “I don’t think this will do any good or bring more harmony to Europe.”

Despite repeated requests for comment, none of the major Islamic umbrella organizations in Europe had responded by presstime. However, some exceptions notwithstanding, Muslims are generally thought by analysts to oppose the notion of legislating Sunday rest.

While most European Seventh-day Adventist officials who spoke with Liberty recognized the legitimate health and family issues raised by Sunday-rest proponents, they also expressed serious concerns. “The problem will come when SDAs who work now on Sundays in order to have their Sabbath free will be asked to work on Saturday,” says Pastor Karel Denteneer, responsible for Public Affairs and Religious Liberty (PARL) with the church’s Belgian-Luxembourg Conference.

The idea of a day for all of society to rest is, of course, biblical, Denteneer points out—at least in old Israel, in a Jewish context. “To impose this today in our society to nonbelievers, Friday keepers and Sunday keepers and so many other religions stands diametrically opposed to the basic principles of religious liberty, which guarantee freedom of belief,” he adds. “So I guess we will continue to live in this tension between promoting the Divine requirement of observing the biblical Sabbath day and respecting all other observances.”

Denteneer also notes that traditional SDA Bible scholars still interpret the prophecies of Daniel and Revelation, well outlined in the writings of church pioneer and visionary Ellen G. White, as pointing to a Sunday-Sabbath issue playing a crucial part in the last days before the second coming of the Lord. “According to the traditional interpretation, some will keep the Sunday for religious motives—the ones marked at the front of their head—and others will keep Sunday for social practical reasons—the ones marked at their right hand,” Denteneer explained.

The big risk at this point, Denteneer continued, is that someday “democracy” could sacrifice the basic tenets of religious liberty under the guise of a “higher motive.” And the potential danger is indeed realistic. In fact, he thinks the Sunday-rest effort—because it is built on a wide platform of believers and nonbelievers across all 27 EU member states—will eventually succeed.

“For that reason our church will continue with more zeal than ever before to take a stand for religious liberty. We should try to get even more involved in the debate at an official level,” Denteneer says. “For the moment no official action has been undertaken by our church officials to any possible vote.”

Of course, the effort to enshrine Sunday as the state-sanctioned day of rest is not limited to Europe. In the United States a movement to have similar restrictions enacted is also growing stronger. At least for now, however, the primary epicenter of the showdown between opponents and supporters of Sunday rest appears to be centered in Brussels.