The Demos and Religious Freedom

Bal Harbor September/October 2011

It's a geographical fact, based on the geometry of the earth, that springtime in one part of the world means cold weather in another. Though an analogy only, it fits what's being hailed as the "Arab Spring," the uprisings that have either toppled or challenged the rule of dictators throughout the Arab world, from North Africa to the Persian Gulf and even into Mesopotamia.

The metaphor for "spring," of course, entails hope, promise, new life, and a new beginning. However, even while the outcome in some nations is still uncertain, such as Syria and Libya—where the winter isn't leaving so easily (and not without plenty of blood, either)—in places where "spring has sprung," some signs are already not so hopeful that the sunshine is going to last long, if at all. In other words, the flush of freedom that democracy is supposed to usher in isn't turning out as many had imagined.

In fact, for many citizens, especially the Christian minorities in these countries, "spring" threatens them with harsh, even deadly, weather.

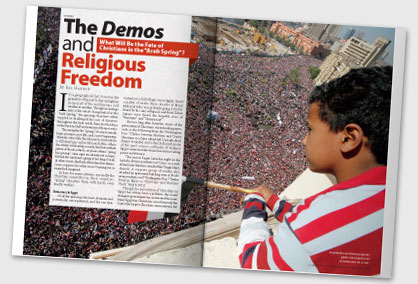

A boy watches as pro-democracy supporters gather in Tahir Square in Cairo.

Reuters/Mohamed Abd El-Ghany

Democracy in Egypt

Of all the uprisings, the most dramatic and potentially consequential, and the one that started out so full of hope, was in Egypt. In just a matter of weeks, three decades of Hosni Mubarak (who was probably going to be followed by his son) collapsed, and from Tahrir Square were heard the hopeful cries of "Freedom!" and "Democracy!"

Not too long after, however, stories of the persecution of Christians started making news, such as the following from the Washington Post: "Clashes between Muslims and Coptic Christians in a Cairo suburb left 12 people dead, dozens wounded, and a church charred in one of the most serious outbreaks of violence Egypt's interim rulers have faced since taking power in February.

"The unrest began Saturday night in the Imbaba district northwest of Cairo, as a mob of hard-line Muslims attacked the Virgin Mary church. A separate group of youths also attacked an apartment building several blocks away, residents said" Washington Post, ("Twelve Dead in Egypt as Christians and Muslims Clash," May 8, 2011).

Though the persecution of Christians in Egypt has always been a problem, the recent change in government has accelerated the issue. Many Egyptian Christians, most famously the Copts (the largest Christian community in the Middle East, and who have been in Egypt since the early centuries of Christianity), worry about what a democratic Egypt might hold for them. The big question remaining, once elections are held, is What happens if, as many expect, Islamist parties, such as the Muslim Brotherhood, start gaining control? Christians in Egypt do not expect to fare well under them or under any Islamist group that gains power, especially through democratic means.

They have good reason to fear democracy too. Assuming fair elections were held, what could be expected in a democracy where, according to a 2010 Pew Research Center survey, 84.5 percent of Muslim Egyptians who make up about that percentage of the population—a healthy majority even by American standards—believe that those who convert from Islam to Christianity or any other faith should be publicly executed? An even larger majority, 95 percent, believes that Islam should play a large role in the politics of the new Egypt. If so, democracy could bode very badly for the Christian minority there, especially given the few precedents already seen.

Iraq and the Palestinian Territories

Whatever the ultimate outcome of the Iraq War, the biggest losers (besides Saddam's immediate Baathist clique) have been Iraq's Christians, who have found life under the new democracy so unbearable and dangerous that many have fled. It's estimated that half of Iraq's Christians have left the country since the ouster of Saddam. Even with the large American presence there, many Christians don't feel safe in Iraq, which—unlike its neighbors—had its own "spring" imposed on it by hundreds of thousands of outsiders funded by billions of dollars.

"Before the U.S.-led invasion in 2003 there were about 1.4 million Christians in Iraq, a Muslim-dominated nation of nearly 30 million," said an online USA Today article. "Since then, about 50 percent of Iraq's Christians have fled the country, taking refuge in neighboring Jordan, Syria, Europe, and the U.S.A., according to the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC)" ("For Christians in Iraq, the Threats Persist," updated June 2, 2010, http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/iraq/2010-06-01-iraq-christians_N.htm?loc=interstitialskip.

The article continued: "Here in northern Nineveh province, life for Iraq's diminishing Christian community is particularly bleak. At least 5,000 Christians from the provincial capital of Mosul fled the city after targeted attacks in late 2009 and early this year left at least 12 Christians dead."

Mourners at St. George Chaldean Church in Baghdad stand beside the van carrying the coffins of two victims killed in December 2010 bomb attacks. Reuters/Mohammed Ameen

All this, meanwhile, as thousands of American troops still remain. What might happen when these troops do leave is something that many of Iraq's Christians have decided not to hang around and find out for themselves.

Also, after democratic elections in the West Bank and Gaza, the prospects for religious freedom for Christians haven't been too promising, either. A State Department report on religious freedom in the Palestinian Authority-administered (PA) areas warned: "The PA did not take sufficient action . . . to remedy past harassment and intimidation of Christian residents of Bethlehem by the city's Muslim majority. The PA judiciary failed to adjudicate numerous cases of seizures of Christian-owned land in the Bethlehem area by criminal gangs. PA officials appear to have been complicit in property extortion of Palestinian Christian residents, as there were reports of PA security forces and judicial officials collud[ing] with gang members in property extortion schemes. Several attacks against Christians in Bethlehem went unaddressed by the PA."

According to the report, Christians under Hamas aren't faring any better. Or, to be more specific, Christians under the democratically elected government of Hamas aren't faring any better. Did anyone really expect them to?

Syria

As of this writing, President Bashar al-Assad is still securely in power, despite widespread and vociferous protests that his regime has been brutally repressing. Amid all the chaos, however, Syria's Christians are exceedingly worried about their fate should the "Arab Spring" reach its borders too.

Syria has a Christian community that dates back to the earliest days of the faith. The apostle Paul's famous conversion happened on "the road to Damascus"; Damascus was the first place he went to after that experience; and in that city he was baptized (see Acts 9).

Whatever else one could say about the al-Assad regime, it has enforced a strict secularism on the country. (Many remember his father's brutal massacre of thousands in 1982, in which the Syrian army all but demolished the city of Hama, in a successful squashing of the Muslim Brotherhood, the same group who appears to have the most to gain from Egypt's new democracy.) This secularism, however undemocratic, has benefitted the nation's Christians, which have for many years enjoyed a peaceful, even prosperous existence.

Bashar al-Assad has maintained very good relations with Syria's Christians, even visiting their communities to pray and pass on messages of goodwill. Christians, about 10 percent of the population, hold a disproportionally high number of senior positions in the government and make up a large professional class of doctors, dentists, and engineers. Now, though, with so much uncertainty, many are fearful. In fact, already weddings have been canceled and Christians have become much more low-key, all out of fear of extremist elements within the Muslim community, the same groups that are working so hard to overthrow the present regime.

Here, as everywhere the revolts have been taking place, large, gaping, and fearful questions remain about whether the old despotic regimes will be replaced by new despotic ones, even if democratically elected, because democracy is no guarantee of freedom.

On the contrary . . .

The Demos

As the world watches these events unfold, many mistakenly equate the word "democracy" with "freedom," a potentially disastrous link. The concepts are not synonymous; democracies can be the most despotic of all forms of government, because they come with an aura of legitimacy. After all, it was what the people, the demos, wanted, and they proved it by how they pulled the lever at the polls. Democracy does not automatically translate into freedom. As far back as fourth century B.C., Plato railed against the inherent dangers of democracies, calling it one of the worst forms of government imaginable.

America's founders understood this danger as well, which is why they purposely built into their new government numerous mechanisms with the express purpose of limiting the power of the demos. Besides the divided government—with one branch, the Supreme Court, almost completely out of the democratic process—a powerfully striking example of how they sought to curtail the "power of the people" is the electoral college for presidential elections, which explain why, in a few cases, the candidates who had the highest popular votes were still denied the presidency.

Also, from the ratification of the United States Constitution, in 1787, to the Emancipation Proclamation, in 1863, millions of Americans were kept in abject slavery—all under a democratically elected government in Washington. And even then it took the brutality of the Civil War and the death of hundreds of thousands of Americans in order to free the slaves in democratic America. That is, it took a war to do what the people wouldn't do at the voting booth.

It was still, then, another hundred years before many segments of the American democracy would allow fellow citizens to sit in the same restaurants, sit in the same trains, or even sit in the same part of the bus as other citizens did. In fact, it took the U.S. Supreme Court, the most undemocratic branch of our government, to do what American democracy still wouldn't do, and that was get rid of the repressive nonsense about "separate but equal" when it came to American public schools. America's Black community has known, historically, firsthand the potentially ugly and dangerous side of democracy.

If even after almost 200 years American democracy still couldn't get it totally right, who but the most Pollyanna-ish are going to expect anything better in the Arab world, where decades of repression has fueled a simmering fanaticism? One can be hopeful, and the West should do what it can to help, but what can it expect from a region in which, almost daily, people blowing themselves up (along with others) in the name of religion, not in the name of "Jeffersonian democracy," "church-state separation," and "religious liberty"?

Hence, the fear that many Christians in the region have about the "Arab Spring." All things considered, they have good reasons to, especially if the outcome of that "Spring" is determined by a demos with little or even no understanding of, or sympathy for, religious liberty.