The Question of the Common Good

Douglas Morgan January/February 2010For much of the twentieth century, observers of American political culture could dismiss apocalyptic prophecy as a preoccupation thriving only on the paranoid fringes of national life. Nearly a decade into the twenty-first century, though, such a view is long past. The phenomenal commercial success of the Left Behind books and films put the spotlight on the longstanding influence of dispensationalist premillennialism in predisposing conservative Evangelicals to favor an assertive American military stance, particularly in regard to defense of the state of Israel.

During the era of Liberty magazine’s predecessor, the American Sentinel, more than a century ago, dispensationalism was just beginning its rise to predominance among conservative Protestants. However, other forms of millennialism thrived as powerful influences in that era’s struggle over the position of Christian identity and morals in the nation’s political realm.

The postmillennialism of the Second Great Awakening led to revival and social reform as the path to a millennium of peace and righteousness, after which Christ would return. In the late nineteenth century it still exerted considerable influence. This was the form of millennialism that animated “the Christian lobby”—the moral reformers of such organizations as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the National Reform Association (NRA).

The American Sentinel and the National Religious Liberty Association were part of the new Seventh-day Adventist Church. The church was an outgrowth of the Millerite movement, which derived its driving force from the older, historicist form of premillennialism and saw the fulfillment of biblical prophecy in a progression of historical developments through the centuries, including the rise and eventual fall of the American republic. Adventists thus did not believe that the legislative proposals of the Christian lobby, which came before Congress in 1888 in the form of a national Sunday rest bill and a proposed constitutional amendment requiring public schools to teach the principles of the Christian religion, would lead a reformed America toward the millennial era. Instead, such use of legislative coercion on behalf of religious ideals would lead to the demise of the republic and the liberty it espoused.

American Sentinel coeditor Alonzo T. Jones came to Washington in December 1888 to present his argument against Senator Henry W. Blair’s national Sunday observance bill to the Committee on Education and Labor that Blair chaired. As discussed in part 2 of this series, Jones’ central argument was that the religious nature of Senator Blair’s Sunday rest bill made it unconstitutional. He buttressed that main point with two other lines of argument, which he called “practical” and “historical”—and it is in the latter, especially, that we find the primary source of his intense motivation.

Among the practical arguments, Jones cited the economic unfairness of Sunday laws to observers of a Saturday Sabbath, who are compelled either to give up one sixth of their productive time, or violate their religious convictions. A proposed exemption for “Seventh-day believers” would solve nothing. Acceptance of an exemption clause would mean conceding the central principle and acknowledging the authority of Congress to legislate in connection with the observance of rest days. A Sunday law with an exemption would still make “every man’s observance of Sunday, or otherwise, simply the football of majorities.” It would reflect mere toleration of difference, not recognition of human right.1

This and other practical arguments concerning the inconsistencies and unintended consequences of such legislation strengthened the force of Jones’ case. The historical line of argument, though, showed that a greater concern than potential loss of income was at stake. It was conviction about the direction of history and their role in its climactic drama that made Adventists the most energetic and unrelenting opponents of Sunday laws and related measures.

Jones built his historical argument on an analogy from Roman history. In his introduction to the committee, he identified himself as a professor of history at the Adventist Battle Creek College in Michigan, where, alongside his editorial work, he had just completed his first semester of teaching. Jones the professor also became a prolific historical writer, displaying impressive immersion in church history and effectiveness in construction of clear, persuasive argument.

A decade before America’s imperialist venture in the Spanish-American War made it more commonplace to do so, Jones developed a comparison between the trajectory of American history and that of ancient Rome. However, Jones focused not so much on the transition from republic to empire as he did on the late empire’s synthesis with the Christian church. Drawing especially on the work of the noted German church historian August Neander (1789-1850), Jones portrayed for the Blair committee how a progression of Sunday laws in the fourth and fifth centuries A.D. functioned as a critical mechanism for bringing about the linkage of church and empire that characterized medieval European Christendom.2

After the emperor Constantine ended the persecution of the church and began bestowing imperial favor upon it, the bishops accepted the emperor’s arbitration in resolving theological disputes, most famously at the First Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325. In his General History of the Christian Religion and Church, though, Neander emphasized the agency of the bishops in this new collaboration with the empire—“their determination to make use of the power of the state for the furtherance of their aims.”

Constantine’s Edict of 321, which ordered that “judges and townspeople and the occupation of all trades rest on the venerable day of the sun,” but exempted agricultural work, constituted an initial step in the bishops’ cultivation of power. According to the fifth-century church historian Sozomen, the law had a religious intent—“that the day might be devoted with less interruption to the purposes of devotion,” though it must be noted that the language of the decree, referring to Sol Invictus rather than the Christian God, makes the object of that devotion ambiguous at best.3

By the reign of Theodosius I (379-395), matters were becoming much clearer, as Christianity defined by Nicene orthodoxy progressed from the status of favored religion to become the only legal religion of the empire. As part of that process, a Sunday law of 386 extended earlier restrictions on Sunday labor and business transactions much further and implemented more rigorous enforcement.

With Sunday increasingly free from labor, Jones told the committee, the circuses and theaters throughout the empire became more crowded than ever on Sundays, prompting a council of bishops meeting in Carthage in 401 to send a resolution to the emperor calling for a rescheduling of “public shows” on days other than Sunday and feast days. Because “the church could not then stand competition,” “she wanted a monopoly,” he declared. The desired law requiring that circuses and theaters be closed on Sundays finally came in 425, its stated purpose being “that the devotion of the faithful might be free from all disturbance."4 Thus, as Jones presented it, Sunday laws were instrumental in the gradual ratcheting up of the church’s reliance on the coercive power of the state in the Constantinian revolution.

Capping the process, the “theocratical theory,” which Neander had identified as driving the bishops’ agenda since the time of Constantine, gained a powerful theological rationale when one of the most influential thinkers in church history, Augustine, defended the use of coercion in the Catholic Church’s struggle against the heretical Donatists in North Africa. In the words of Neander, Augustine’s rationale for using force on behalf of the church “contained the germ of that whole system of spiritual despotism . . . which ended in the tribunals of the Inquisition.” But Jones stressed that Augustine’s “infamous theory” was “only the logical sequence of the theory upon which the whole series of Sunday laws was founded.” It worked this way:

“The church induced the state to compel all to be idle for their own good. Then it was found that they all were more inclined to wickedness. Then to save them from all going to the devil, they tried to compel all to go to heaven. The work of the Inquisition was always for love of men’s souls, and to save them from hell.”5

Jones’ emphasis on Sunday laws as the mainspring driving the union of church and empire in ancient Rome might not as easily convince historians today. But clearly, such enactments were integral to the development of what twentieth-century scholar John Howard Yoder called “that fusion of church and society of which Constantine was the architect, Eusebius the priest, Augustine the apologete, and the Crusades and Inquisition the culmination.”6 The Adventists’ apocalyptic reading of history intensified their belief that the same process was at work in the drive for a national Sunday law in late nineteenth-century America. That was the foremost reason Jones and the American Sentinel were determined to do something about it.

The 1888 Sunday law “crisis” also prompted the Seventh-day Adventist Church to a new level of grass roots organization. The denomination’s International Tract Society, working through its state-level societies, distributed petitions to the church members, urging them not only to sign but to canvass their friends and neighbors for signatures as well. By March 1889 they had amassed 260,000 signatures in opposition to the national Sunday bill, presented in large stacks of files—one each for the House and the Senate—bound in patriotic red, white, and blue fastenings.

Presentation of the stack of files in the House created a “quite interesting” scene, according to a report in The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald. When by prior arrangement pages delivered the three-foot-high stack to the desk of Representative O’Donnell of Michigan, his head barely appeared above it. The Adventists claimed that all 260,000 of their names came with the individual signatures of voting-age citizens. By contrast, their opponents had only 407 individual signatures, which pledged the support of the various churches and associations, upon which the claim of 14 million names was based.7

In the meantime Senator Blair also brought before his committee his proposal for a constitutional amendment requiring the states to provide free public education that included instruction in “the principles of the Christian religion.” Jones returned to Washington in February 1889 to speak against this effort to “Christianize” both the public schools and the U.S. Constitution with one stroke. In contrast to testimony in favor of the amendment from several Protestant clergymen, including members of the Evangelical Alliance, Jones contended it would establish Protestantism as the state religion.The public schools would become “seminaries for the dissemination of Protestant ideas,” which would “violate the equal rights of Catholics, Jews, and infidels.”8

This variation on a “Christian amendment” went nowhere, though another attempt in a different form created a larger stir in the 1890s. Also, Senator Blair’s efforts to get the national Sunday rest bill reported out of his committee for a vote on the floor were frustrated. On the final day of the congressional session in March he tried to get the bill to the floor with a discharge petition, but the opposition of one senator—all that is required—blocked the maneuver.9

The Christian lobby, however, was a long way from accepting defeat on Sunday legislation, and the Adventists, conversely, continued to step up their organization of resistance. They organized the National Religious Liberty Association in July 1889, dedicated to the same agenda as the American Sentinel.10 Through name changes and structural modifications, the organization continues to the present in the form of the International Religious Liberty Association and associated entities throughout the world, such as the North American Religious Liberty Association.

The new organization mobilized Adventist advocacy that helped thwart new attempts at national Sunday legislation in 1889 and 1890. Senator Blair introduced a revised measure in the Fifty-first Congress, designed to neutralize Jones’ most telling arguments from the previous December. Overt religious language was minimized and an amendment for Saturday-observers included. None of this altered the foundations of Jones’ opposition, however, and he had no trouble locating abundant evidence of unconstitutionality. And, the Adventists this time came up with 500,000 signatures in opposition. In 1890 a bill proposed by W.C.P. Breckenridge of Kentucky in the House of Representatives, applicable to the District of Columbia only, likewise kept a narrow focus on the right of employees to one day off from work per week. The primary danger here, said Jones, was the precedent it would set for broader and more dangerous legislation.11

Success for the Sunday-law forces soon came via a different route, though. First, in a decision written for the Supreme Court’s ruling in Church of the Holy Trinity v. U.S. (1892), Justice David Brewer referred to the United States as a “Christian nation,” and cited state and local Sabbath observance laws as part of the evidence for that characterization.12 This decision appeared to put the judgment of the nation’s high court in opposition to the foundational principle upon which A. T. Jones and the American Sentinel had stood from the beginning—namely, the neutrality of the federal government with regard to religion.

Jones saw the “Christian nation” decision as a dramatic step toward the final apocalyptic crisis scripted by the book of Revelation. In his intricate interpretation of the prophecy of Revelation chapter 13, verses 11-18, a passage that Adventists believed directly concerned the United States, the decision signaled the formation of an “image to the beast.” The demise of the constitutional principle against the federal government’s endorsement of a particular religion opened the way for a repressive union of church and state like that of medieval Europe.

A series of dramatic sermons preached by Jones to Adventism’s largest congregation, the Battle Creek Tabernacle, in May and June of 1892 nicely illustrates the impact of this set of intense beliefs about apocalyptic prophecy. With the “image to the beast” now formed, declared Jones, only one small step remained in the fulfillment of Revelation 13 and the final crisis of religious persecution that would immediately precede the second coming of Christ. Some further event would “give life” to that image, as described in verse 15.

Jones did not know just when this latter development would occur, but he reminded his hearers of their task in the interim: to use their resources and institutions to the fullest in giving the warning message to the world. The shortness of time, he argued, does not make the church’s institutions obsolete; rather, “because time is so short, we need more institutions and more means.”13 Thus, rather than a call to hunker down and passively observe the unfolding of predetermined events, the signs that the end was nearer than ever constituted a call to greater action than ever on behalf of the values—such as liberty—to be championed by a people preparing to meet their Lord in peace. On top of all that, a recent Christ-centered revival opened to believers, if they would receive it, the spiritual power needed for faithful witness through a final crisis.14

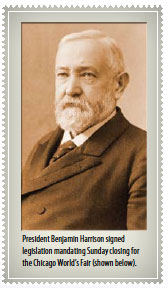

Then, less than three months later, another event seemed to give dramatic confirmation to Jones’ analysis of the times. On August 5 President Benjamin Harrison signed the first piece of federal legislation mandating Sunday closings. After an intense spate of advocacy led by the NRA and WCTU, Congress passed a law that made federal appropriations to the Chicago World’s Fair contingent on the fair closing its doors on Sundays.15

Wilbur F. Crafts called it “the greatest moral victory since emancipation [from slavery].”16 Alonzo T. Jones viewed the action as having at last given life to “the image of the beast.” In itself threatening no one with death or even imprisonment, the law put into action the illicit union of church and state sanctioned by the Holy Trinity decision.17

Both men were proved wrong in seeing the measure as the prelude to an imminent millennium. Though a victory for the Christian lobby, it fell far short of the provisions of the national Sunday rest bill that had been at the center of the heady push toward a millennial “theocracy” in 1888. For the Adventists, the immediacy of the external threat to religious liberty receded by the mid-1890s. If the urgency of the prophetic impulse driving public activism diminished somewhat, though, it would never disappear from the Adventist outlook. In fact, the 1888-1893 epoch left a permanent legacy for how the editors of the American Sentinel and its successor, Liberty, viewed public events and the corresponding action in the public arena that they advocated. They watched for signs of a reprise of the heightened repression of liberty in society, combined with spiritually energizing revival that would once again bring them to the verge of the final, dramatic conflict between good and evil, followed by the glorious establishment of Christ’s eternal kingdom. As in the 1880s and 1890s, those expectations would do much to propel action for religious liberty and human rights.

A serious issue remains to be addressed, however. If prophecy belief played a major part in motivating Adventists to an oppositional kind of activism that has in turn contributed to the expansion of religious freedom in America, did such beliefs encourage or even allow for a broader and more positive range of action to meet societal need? Put another way, if the American Sentinel can be credited with helping to check the overbearing excesses of some reformers, did it contribute in any way to the kind of organized action to relieve suffering and redress injustice with which the progressive reformers must be credited?

Again here, exploration of the experience of the Sentinel’s most influential editor, Alonzo T. Jones, may lead us to partial answers. Jones’ extensive study of history, politics, and theology, his spiritual ardor, and his rhetorical gifts indeed made him a powerful advocate of religious liberty. Even Senator Blair, who must have tired of Jones’ relentless opposition to his legislative initiatives, remembered the editor some 20 years later “with respect” for his “great ability” and “evident sincerity.”18

But Jones had penchant for pressing his principles to their radical extreme, for holding his positions with individualistic absolutism, and for bombarding his opponents with harsh invective. These traits contributed to conflicts that seriously marred his legacy both within the Adventist movement and in the public arena.

Jones developed the theme of “Christian citizenship” in the early 1890s. Building on the apostle Paul’s statement that “our citizenship is in heaven” (see Philippians 3:20), Jones insisted that truly loyal Christians have transferred their citizenship from earthly government to the heavenly kingdom. While their names remain on the citizenship rolls of earthly government, they are in fact citizens of another country, sojourners in the particular nation-state where they happen to reside in the present age.19

Many contemporary Christian thinkers, such as Stanley Hauerwas,20 would likely welcome this emphasis for its thorough break with conventional, American-style “Constantinianism,” which blends devotion to God with devotion to America, even while church and state remain legally separate. Indeed, this perspective did equip Jones and other Adventist writers for a bold witness against American imperialism during the Spanish-American War. In a time when, according to historian Sydney Ahlstrom, “patriotism, imperialism, and the religion of American Protestants” stood in more “fervent coalescence” than ever before,21 Jones decried the war as national “apostasy from republicanism to imperialism.” The preachers who pronounced blessing on the war, he said, gave evidence of a parallel apostasy in the Christian church. He called for “a revival of the preaching of the gospel of peace,” and bluntly declared that those “preachers that preach war are not the ministers of Christ, whatever their profession may be.”22

As a result of his views on Christian citizenship and separation of church and state, Jones concluded that a clean break with Constantinianism meant not only that the church must not accept public funds for any of its institutions or activities, but it must also repudiate tax exemption. But the Adventist missionaries, who were already trying to establish church work in other political contexts, and the famed Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, who was at that very time seeking tax-exempt status in Michigan for the church’s medical missionary institutions, pushed back at Jones’ unbending policy, and in the end it did not prevail as the denomination’s policy.23

Jones’ blanket condemnation of pro-war preachers as “not ministers of the gospel” is but one example, and a rather mild one, of his rhetorical attacks. By the summer of 1889, Wilbur Crafts became fed up, and he demanded that Jones and coeditor Ellet J. Waggoner be put on trial for “wholesale slander and falsehood” by the congregations in which they held church membership. The June 19, 1889, issue of the Sentinel, he charged, contained “sixty-seven false statements, thirty-seven of them gross slanders, bolstered up by thirty petty slanders.”24

Roman Catholic clerics in particular bore the brunt of Jones’ harsh rhetoric. In an era of pervasive anti-Catholicism, Jones may not have been particularly extreme, but as he monitored the growing Catholic presence in America, he consistently portrayed actions and statements from the hierarchy in sinister, conspiratorial terms.

Such polemical combat frequently drew pleas for caution from Adventism’s spiritual mother and prophetic counselor, Ellen White.“I am pained when I see the sharp thrusts which appear in the Sentinel,” she wrote in a lengthy letter in 1895, pointing out that by such “harshness” we “grieve the Lord Jesus Christ.” In particular, she urged restraint in making “hard thrusts at the Catholics,” for many of them are “most conscientious Christians” who “walk in all the light that shines upon them.”25 Five years later she put it this way:

“If we wish men to be convinced that the truth we believe sanctifies the soul and transforms the character, let us not be continually charging them with vehement accusations. In this way we shall force them to the conclusion that the doctrine we profess cannot be the Christian doctrine, since it does not make us kind, courteous, and respectful. Christianity is not manifested in pugilistic accusations and condemnation.”26

Most remarkable of all, Ellen White gave similar counsel to Jones regarding his interaction with one of the Sentinel’s most powerful opponents in the theocracy-threatening Christian lobby—the WCTU. Herself a temperance lecturer at WCTU rallies, Ellen White had exhorted Adventists to be involved in the organization since the late 1870s. The Adventist prophet fully endorsed political action for prohibition. The liquor traffic, she wrote in the lead article for the November 8, 1881, issue of The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, caused a “moral paralysis upon society,” and that reality placed every temperance advocate under the mandate of exerting influence “by precept and example—by voice and pen and vote—in favor of prohibition and total abstinence.”27

Ellen White did not approve of the WCTU’s shift to a broader political agenda under Frances Willard’s leadership in the 1880s, and she fully supported the American Sentinel’s vigorous campaign to block Sunday legislation. However, she did not see the misguided aspects of the organization’s work as reason for severing connection with it and burning bridges with fiery denunciations.

At the annual meeting of the American Health and Temperance Association held in Oakland in 1887, Ellen White urged her Adventist listeners not to be put off by the WCTU’s new ventures but to view the situation as an opportunity: “You say they are going to carry this [temperance] question right along with the Sunday movement. How are you going to help them on that point? . . . How are you going to let your light shine to the world without uniting with them in this temperance question?”28

Adventists could learn much from WCTU women, Ellen White believed, and at the same time had much to offer them. Realization of this important mutual benefit, she wrote Jones in 1900, required “discretion” and “Christlike tenderness” that would honor the nobility of their work and their spiritual integrity rather than a disputatious spirit that would treat them as enemies of the truth, and thus drive them away.29

In these and other ways, Ellen White tried to prod Jones and the church’s other advocates for religious liberty to a more nuanced and constructive relationship with benevolent reform organizations. This approach, she believed, would open the way for Adventists to make a broader contribution to the well-being of society, while at the same time drawing greater and more respectful attention to the transforming message that Adventism offered every individual.

Jones did make some changes in response to Ellen White’s admonitions. However, Jones’ unyielding individualism contributed much to a break with the denomination, finalized in 1909. He stretched the doctrine of religious liberty to mean that the individual Christian was accountable to no authority structure outside himself—be it congregation, class, conference, synod, council, hierarchy, or anything else. Though he continued to preach and write for small groups of supporters until his death in 1923, Jones experienced the painful reality that no accountability meant, in the end, no community.30

Nevertheless, because the story of the American Sentinel and the prophetic impulse that motivated its witness is Alonzo Jones’ story more than anyone else’s, we must here give him the last word. Whatever the flaws and shortcomings of his work, he did recognize the need to show that his dissenting, apocalyptic form of Christianity, radically free from all the corrupting elements of Constantinianism, was not irresponsible escapism, heedless of the systemic injustice and desperate human need in society.

In his appearance before Senator Blair’s committee in 1889 to oppose the amendment that would “Christianize” the public schools, he did his best to portray how, in the long run, the best way for the church to make an impact on the world and to lead the way toward the millennial dream of a transformed society cherished by the Christian lobby was simply to be the church, uncompromised and unencumbered by any allegiances save to Christ alone:

“Let [the church] prove herself by her works of self-denying charity, to be the true church as Jesus proved Himself to the disciples of John to be the true Messiah, when He told them ‘Go and show John again those things which ye do hear and see; the blind receive their sight and the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up and the poor have the gospel preached to them.’ Let her organize all her forces for a more determined and closer, hand-to-hand, struggle with sin and evil, of every form, and the misery and wretchedness, of which they are the cause. Let her ministers and missionaries not only proclaim from their pulpits ‘the unsearchable riches of Christ,’ but descending among the hungry multitudes, distribute to them the precious bread of life. . . . Let them, by setting forth the beauty of holiness and the purity of ‘the truth as it is in Jesus,’ which is able to make us wise unto salvation, send the healthful and invigorating influences of our holy religion through every social relation. . . . Let them turn these streams of the pure water of life, welling up in the hearts of their followers, into the dark and pestilential receptacles, where ignorance, poverty, misery, and sin are gathered, and breed disorder and death. . . . Then shall be hastened the promised time of the coming of our King, when there shall be a new heaven and a new earth, wherein dwelleth righteousness—the Holy City, New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband, the tabernacle of God with men, where He will dwell with them and they shall be His people, and God Himself shall be with them and be their God.”31

- “The National Sunday Law, Argument of Alonzo T. Jones Before the United States Senate Committee on Education and Labor; at Washington , D.C., December 13, 1888,” pp. 118-122 (American Sentinel tract, 1892), in Religious Liberty Tracts, Online Document Archives, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Office of Archives and Statistics, www.adventistarchives.org/doc-info.asp?DocID=47173.

- Ibid., pp. 67-74.

- Kenneth A. Strand, “The Sabbath and Sunday From the Second Through Fifth Centuries,” in Strand, ed., The Sabbath in Scripture and History (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1982), p. 328.

- “The National Sunday Law,” pp. 69-71.

- Douglas Morgan