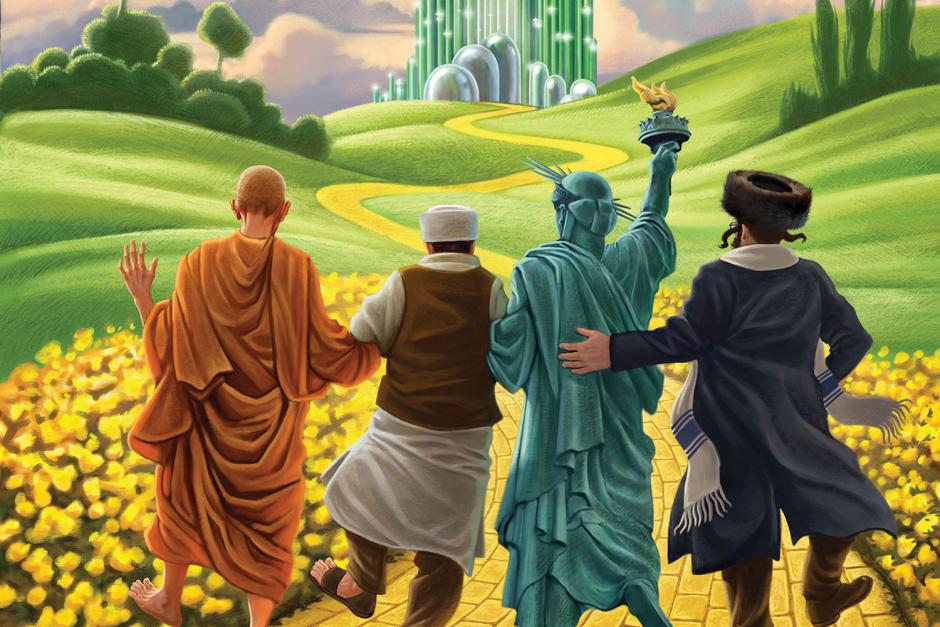

The Road to Freedom

Dwayne Leslie May/June 2017There was little fanfare when then President Obama signed the Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) into law on December 16, 2016. He affixed his signature to the hard-won legislation along with some 50 other bills, ranging from the National Park Service Centennial Act to the Inspectors General Empowerment Act.

Yet for the bipartisan group of religious freedom advocates and religious leaders who had supported IRFA on its five-year, often painfully sluggish journey through the legislative process, it was a moment to savor. Russell Moore, president of the Southern Baptists’ Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, called it an affirmation that religious freedom is “rooted in our deepest commitments as Americans.” And he hoped this update to the first IRFA—passed more than 18 years ago—would help “persecuted religious minorities around the globe will see that they have not been forgotten.”

Bishop Oscar Cantu, chair of the Committee on International Justice and Peace of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, echoed Moore’s thoughts. Cantu summed up the feelings of many supporters of IRFA when he told the National Catholic Register that he hoped the law would “raise the profile of religious freedom, put the international community on notice, and make clear that the people of the United States will be watching.”

But for many longtime religious freedom watchers, these sentiments spark a sense of déjà vu. A quick scan of news reports from late 1998, written in the days and weeks after President Bill Clinton signed the original International Religious Freedom Act into law, reveals similar hopes and expectations.

Advocates then predicted a new era, where the treatment of religious minorities abroad would make a tangible difference in relations between the U.S. and its diplomatic and trade partners. They expressed hopes that religious freedom concerns would be integrated into U.S. foreign policy and filter into the Department of State’s training, strategic planning, and actions. They confidently spoke of religious freedom violations leading to U.S. action, ranging from diplomatic protests to economic sanctions.

These predictions and hopes, though, have largely been dashed.

Any analysis of last year’s update to IRFA must ineitably take place through the lens of these 18 long years of disappointment. Disappointment that the office of ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom—a centerpiece of the original law—has been largely underresourced and marginalized.

Disappointment that the process under IRFA intended to trigger sanctions against countries engaged in particularly egregious violations of religious freedom has remained largely dormant.

Disappointment that, despite the careful infrastructure created by IRFA, Washington has been consistently slow to act in officially recognizing religious atrocities—even the genocidal devastation perpetrated by ISIS against Christians and Yazidis in Iraq.

Disappointment that the impact of IRFA has fallen so far short of the intent of its drafters; that, in the 2013 words of noted religious freedom advocate Thomas F. Farr, IRFA has done little to influence U.S. foreign relations “except perhaps to irritate our banker (China) or our erstwhile ally in oil (Saudi Arabia).” And until changes are made to IRFA, added Farr, “America’s religious freedom policy will remain a powerful idea that has not yet gelled.”1

IRFA Reset

Last year’s update to IRFA represents an attempt, once again, to take the idea of religious freedom from the realm of ideal to the realm of action. This time it has the advantage of hindsight—a somewhat clearer understanding of why, despite high hopes for the 1998 IRFA, religious freedom as an influencing principle has had little actual impact on the processes and policies of the U.S. Department of State.

The updating legislation addresses some major structural issue that many believe contributed to the ineffectiveness of the original framework.

First, it brings the office of the ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom in from the diplomatic wilderness by mandating that the ambassador report directly to the secretary of state rather than to lower-level officials. This raises the status of the ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom to the same level as other at-large ambassadors, such as those for AIDS coordination or global women’s issues. It further bolsters the International Religious Freedom office at the State Department by calling for a minimum number of full-time staff.

The new legislation also mandates religious freedom training for all foreign service officers—as opposed to merely providing it as a training elective. This, many believe, is an especially critical piece of the puzzle. This training exposes the men and women who practice U.S. foreign policy to the many practical ways in which enhanced religious freedom contributes to a nation’s social, economic, and political stability. Thus, diplomats will see how actively supporting religious freedom lines up with core U.S. foreign policy objectives in promoting a more secure and prosperous global landscape.

Other measures in the 2016 IRFA include an enhanced watchdog framework that will supplement the lists and annual reports already produced by the State Department. It establishes an “entities of particular concern” category (mirroring the already-extant “countries of particular concern” category). This will focus on nonstate actors, such as Boko Haram and ISIS and other militant nongovernment entities.

Further, it creates a “designated persons list” to name individuals who engage in religious repression or persecution, and allows the president to institute sanctions against persecutors.

Bigger Questions

The 2016 IRFA is named for former Congressman Frank Wolf—a very fitting recognition of his relentless campaigning, both in, and now out, of office, for stronger U.S. engagement with religious freedom issues abroad. Wolf gave a major speech in May 2016 in Washington, D.C., at the International Religious Liberty Summit2 held at the Newseum’s Religious Freedom Center. [That speech was featured in Liberty recently.] He gave an impassioned appeal for a more proactive U.S. response to religious repressors around the world, and spoke of individuals he had met in some of the world’s most unforgiving environments for religious minorities.

“While our national interests are complex and manifold, we can be assured that it always benefits a great nation to stand boldly with the forgotten, the oppressed, the silenced and the imprisoned,” he said. “If not America, then who?”

This, perhaps, hints at questions that remain lurking, unanswered, behind all the discussions of IRFA. Is this really a job for America? Is pursuing a religious freedom agenda via U.S. foreign policy, with all its potentially messy entanglements and ambiguities, a suitable way to support persecuted religious minorities and nurture a global culture of religious tolerance?

These are legitimate, though complex, questions. At the very least, they should prompt religious freedom advocates to stay alert. There is, without doubt, the potential for compromise of the secular nature of the state and its various mechanisms, or for the distortion of the very principle of religious freedom itself.

But for me, the alternative—inaction—is unacceptable. As the late Elie Wiesel wrote: “We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.” IRFA takes a side. And given the outsized role the U.S. plays within global geopolitics and trade, this is not an inconsequential thing. The law provides new tools for documenting religious freedom violations and potentially enhances the impact of religious freedom concerns within U.S. foreign policy. Seemingly good things, yes, but fraught with political and moral complexity. As a practical matter, any attempt to advance a high moral principle through the somewhat incompatible vehicle of national interest will require ongoing vigilance and review.

Waiting

Will the Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act bring real change to the culture of the State Department? Will it increase the weight of religious freedom issues within the U.S. foreign policy? Will it translate into some tangible step forward for displaced Iraqi Christians, waiting anxiously in camps in Erbil, Lebanon, and Jordan for a sign they can safely return to their homes? For the communities in northern Nigeria, living in fear of unpredictable and deadly assaults from militant Islamists? For the millions of other members of religious minorities worldwide who face ongoing discrimination, dislocation, or worse?

Despite the intent of the law’s drafters and the ardent hopes of its supporters, any success will ultimately be dependent on its application.

How precisely will Secretary Rex Tillerson and the ambassador-at-large understand and apply the requirements of the law? Will the Trump administration now follow the lead of its predecessors in adopting as narrow an interpretation as possible of its responsibilities under IRFA? As with the 1998 law, we must wait and see. Only the coming years will reveal whether the aspirational intent of the 2016 IRFA law will survive its implementation.

Illustration by Greg Newbold

1 https://www.firstthings.com/article/2013/11/our-failed-religious-freedom-policy

2 https://www.libertymagazine.org/article/the-cries-of-the-persecuted1

Article Author: Dwayne Leslie

Dwayne Leslie, Esq., is director of legislative affairs for the world headquarters of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Silver Spring, Maryland.