The Shaming of Religion

John W. Whitehead January/February 2010

Religion and religious expression have been objects of censorship in the public schools for quite some time. However, the intolerance of anything related to religion has taken a turn for the absurd in recent years.

Much of the credit for this state of affairs can be chalked up to those who have been relentlessly working to drive religion from public life in America. John Leo, a former contributing editor at U.S. News & World Report, paints a particularly grim picture. Written in 2002, his article was an eerie foreshadowing of our current state of affairs:

“History textbooks have been scrubbed clean of religious references and holidays scrubbed of all religious references and symbols. Some intellectuals now contend that arguments by religious people should be out of bounds in public debate, unless, of course, they agree with the elites.

“In schools the anti-religion campaign is often hysterical. When schoolchildren are invited to write about any historical figure, this usually means they can pick Stalin or Jeffrey Dahmer, but not Jesus or Luther, because religion is reflexively considered dangerous in schools and loathsome historical villains aren’t. Similarly, a moment of silence in the schools is wildly controversial because some children might use it to pray silently on public property. Oh, the horror. The overall message is that religion is backward, dangerous, and toxic.”

Unfortunately, things have gotten only worse since John Leo wrote those words. As we have seen all too clearly, Christians of all ages are increasingly finding themselves subjected to censorship and discrimination.

A plea for help from Kathryn, a parent in Colorado, is a perfect example of what’s happening in America’s public schools. Kathryn’s son, Wade, is in the fourth grade. His class was given a “Hero” assignment, which required each student to pick a hero, research the person, and write an essay. The student would then dress up and portray the chosen hero as part of a “live wax museum” and give an oral report in front of the class.

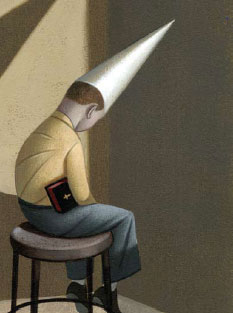

When 9-year-old Wade chose Jesus Christ as his hero, school officials immediately insisted that he pick another hero. After Kathryn and her husband objected, the school proposed a compromise: Wade could write the essay on Jesus. He could even dress up like Jesus for the “wax museum.” However, he would have to present his oral report to his teacher in private, with no one else present, rather than in front of the classroom like the other students. The message to young Wade, of course, was twofold: first, Jesus Christ is not a worthy hero, and second, Jesus is someone to be ashamed of and kept hidden from public view.

This is not an isolated incident. I have been contacted by a number of parents whose children are being subjected to the same kind of treatment in the schools. For instance, a third grader at an elementary school in Las Vegas, Nevada, was asked to write in her journal what she liked most about the month of December. When the little girl wrote that she liked the month of December because "it’s Jesus’ birthday and people get to celebrate it," her teacher tapped her on the shoulder and told her that she was not allowed to write about religion in school. And a teacher in a Pennsylvania public school was told that she could not post a picture of the Statue of Liberty in her classroom because it has the words “God Bless America” at the bottom.

It makes no difference that the material in question does not proselytize, or, as we have seen, that it was presented to people who by and large do not know that it was religious, or even that it is not meant to be religious. What matters is what school officials consider to be religious.

A ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in Nurre v. Whitehead, which affirms the right of school administrators to censor material that has the remotest connection to religion, illustrates exactly how outlandish things have become.

At Henry M. Jackson High School in Snohomish County, Washington, the senior members of the woodwind ensemble, the top performing instrumental group, traditionally select a piece each year to perform during graduation ceremonies. Having performed Franz Biebl’s “Ave Maria” at a public concert in 2004, the seniors in the wind ensemble unanimously chose to perform it again at their graduation ceremony on June 17, 2006, because they felt its aesthetic beauty and peacefulness would be appropriate for the tone of the ceremony.

As Kathryn Nurre, a member of the ensemble, explained, “It’s the kind of piece that can make your graduation memorable because we actually learned to play it really well. And we wanted to play something that we enjoyed playing.”

The student musicians proposed to perform Biebl’s piece instrumentally: no lyrics or words would be sung or said, nor did the senior members intend that any lyrics would be printed in ceremony programs or otherwise distributed to members of the audience. However, despite the absence of lyrics, the school superintendent, Carol Whitehead, refused to allow the ensemble to perform “Ave Maria” at their graduation ceremony because she believed the piece to be religious in nature.

Ironically, the superintendent reportedly didn’t even know that the words “Ave Maria” are Latin for “Hail Mary.” Nevertheless, determined to avoid offense, despite the fact that this Biebl version of “Ave Maria” is not one that most people would even recognize, the superintendent banned it.

Believing that school authorities had violated her right of free speech, Nurre turned to us at The Rutherford Institute. We filed a First Amendment lawsuit against the school in federal district court in June 2006. A year later, a federal district court ruled that the school’s actions were “reasonable” in trying to avoid offending anyone.

In a 2-1 ruling that was handed down in September 2009, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals concurred. According to the court, school authorities can deny students’ rights to free speech just to keep some of those attending graduation from being offended.

However, in a dissent that is notable for its lucidity, Judge Milan D. Smith insisted that Nurre’s right to free speech had been unreasonably violated. “In prohibiting Nurre and her classmates from playing their selected piece of music, the school district misjudged the establishment clause’s requirements and, in so doing, violated Nurre’s First Amendment rights,” observed Smith. He continued:

“I am concerned that, if the majority’s reasoning on this issue becomes widely adopted, the practical effect will be for public school administrators to chill—or even kill—musical and artistic presentations by their students in school-sponsored limited public fora where those presentations contain any trace of religious inspiration, for fear of criticism by a member of the public, however extreme that person’s views may be.

“The First Amendment neither requires nor condones such a result. The taking of such unnecessary measures by school administrators will only foster the increasingly sterile and hypersensitive way in which students may express themselves in such fora, and hasten the retrogression of our young into a nation of Philistines, who have little or no understanding of our civic and cultural heritage.”

In an attempt to avoid offending anyone, America’s public schools have increasingly adopted a zero-tolerance attitude toward religious expression. The courts have not helped, allowing schools the discretion to let an offended minority control a cowed majority. Such politically correct thinking has resulted in a host of inane actions, from the Easter Bunny being renamed “Peter Rabbit” to Christmas concerts being dubbed “Winter” concerts, and some schools even outlaw the colors red and green, saying they’re Christmas colors. And now, simply because someone is offended by the title, students cannot play music that has no words and is performed with no religious intent.

What school officials and the courts fail to understand is that by agreeing to sanitize the schools of anything remotely related to religion, they will not only be silencing an entire segment of the population, but will also be contributing to a cultural wasteland bereft of a rich heritage of Western art, music, and literature—all of which, at one time or another, has been greatly influenced by religion.

Where do our children learn about culture, things such as fine art, classical music, great literature, and anything else that really has substance? They surely don’t find true culture in strip malls, video games, designer clothing, or movie theaters. Unless their parents make an effort to teach them about the traditions of Western culture, children hardly ever encounter anything more complex than a comic book unless schools teach them about this history.

Religion is such an innate part of American culture that it would be impossible to create a strictly secular course of study for students.

For example, if someone complains about Michelangelo’s art because it was so often themed on Christianity, does this mean that we are supposed to have art history books without the Sistine Chapel? What about other masterpieces such as Da Vinci’s Last Supper? For that matter, what about great writers such as Charles Dickens, Alexandre Dumas, or Edgar Allen Poe?

Some of Western civilization’s greatest music was inspired by religion or created for a religious purpose, composed by such maestros as J. S. Bach, Wolfgang Mozart, and Joseph Haydn. Even contemporary artists could find their music banned in schools under such a rubric. For example, the Beatles are visited by Mother Mary in “Let It Be”; Led Zeppelin writes of a “Stairway to Heaven”; and even Jon Bon Jovi sings about “Livin’ on a Prayer.” Such a course of action would reduce American culture and arts education to a sterile wasteland.

Just as with religion, art has always been a matter of personal experience. Each person brings their own experiences and interpretations to art, rendering it nearly impossible to establish a litmus test for what constitutes “religious art” as opposed to secular art.

Anyone who has ever appreciated a book, painting, symphony, or even a newspaper article, movie, or television show should be repulsed at the idea of government officials dictating what art is—and, more important, what it is not. Anyone who has ever appreciated even a comic book should cringe at the thought of letting the government control it.

This brings us back to the Ninth Circuit’s ruling in Nurre. We are witnessing the emergence of an unstated yet court-sanctioned right, one that makes no appearance in the Constitution and yet seems to trump the First Amendment at every turn: the right not to be offended. Yet there is no way to completely avoid giving offense. At some time or other, someone is going to take offense at something someone else says or does. It’s inevitable.

Each time we allow political correctness to triumph over our constitutional freedoms and basic common sense, we are complicit in undermining the freedoms on which this nation was built. And, in a case such as that of Nurre v. Whitehead, we will destroy our culture as well.

Article Author: John W. Whitehead

John W. Whitehead, founder and president of the Rutherford Foundation, writes from Charlottesville, Virginia.