The Trail of Crocodile Tears

Clifford R. Goldstein September/October 2017Most people have heard the phrase “the Young Turks.” The appellation first came to prominence, in American politics in the early 1960s, when it referred to some Republicans in Congress who, upset with the status quo, sought to bring radical change to the party (among these “Young Turks” were Gerald Ford, Donald Rumsfeld, and Melvin Laird). Since then, the phrase has taken on a life of its own, referring to any group of people who, within a system, political or otherwise, seeks to bring radical change.

At the same time, a few people have heard the phrase “starving Armenians” as well.

What most people don’t know is that the two phrases, “the Young Turks” and “starving Armenians,” are in their original context related. It was the scheming of the original “Young Turks” that brought about the twentieth century’s first mass murder on a genocidal scale, the Armenian Massacre, which itself led to the phrase “starving Armenians.”

What happened in the Armenian Massacre, what are its implications for today, and what lessons can we take from it?

The Historical Background

Almost everyone knows about Armenia, even if most can’t find it on a map (it’s in the Caucasus region of Eurasia). Not being able to find it which isn’t surprising, because for much of recent history it didn’t have well-defined borders.And yet the nation itself has a long heritage, going back to about 800 B.C., and in the early centuries A.D. it was the first nation to adopt Christianity as the official state religion.

However, in the centuries that followed, Armenia was part of one empire or another, until the 1400s, when it was absorbed by the Ottoman Turks. The Ottoman rulers, like most of their subjects, were Muslim, and though permitting religious minorities such as the Armenians some autonomy, they also subjected them and other “infidels” to unequal and unjust treatment. Armenians were systematically discriminated against, did not have the same rights as Muslims, and were treated as second-class citizens.

Despite their stature, however, the Armenians did well under the Ottomans. The Armenians tended to be better educated and wealthier than their fellow Turks, which caused some animosity between them and the Turkish majority.Also, fear existed that because many Armenians were Christian, their loyalties would be more with their Eastern Orthodox Russian neighbors to the north than they were to their Ottoman overlords, a fear not entirely unfounded, as World War I would show.

By the nineteenth century, however, the Ottoman Empire was coming apart, and by 1914 it had lost its lands in Europe and Africa. This collapse included the consistent loss of territory to nationalist movements in the Balkans, whose new Christian rulers, not wanting any more fights with the Ottomans, killed or drove out as many Muslims as they could. When Bulgaria became independent in 1878, hundreds of thousands of Muslim civilians fled toward Istanbul, with many dying along the way. Meanwhile, the Christian Armenians were echoing nationalist sentiments as well, and thus were deemed a threat to Ottoman hegemony.

The first massacre, a precursor to the big one that would follow about 20 years later, occurred during the reign of the sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876-1909).Between 1894 and 1896 he instigated a series of pogroms throughout the empire that were intended to break the back of Armenian aspirations for political autonomy.Though hard numbers are not easy to come by, hundreds of thousands were killed.

The Young Turks

As the Ottoman Empire continued declining, a group of reformers in Turkey, who called themselves the Young Turks, overthrew Sultan Abdul Hamid and established a more modern constitutional government, in hopes of saving the Ottoman legacy. Though instituting a few liberal reforms, they ended up becoming fiercely nationalist, advocating the formation of an exclusively Turkish state and even an expansion of the borders in order to reconquer lands in which Turkish residents had come under Russian hegemony.This desire for territorial expansion helps explain why, when World War I broke out, in 1914, they joined with the other Central Powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary, and declared war on Russia and its Western allies, Great Britain and France.

Whatever hopes the Young Turks had of regaining lost land, however, were soon dashed by a string of catastrophic military setbacks.What didn’t help matters either was that Armenians volunteer units fought with the Russians against the Ottomans.This act, viewed as treachery, kindled even more animosity against the Armenians, who were viewed as a clear and present danger to the Turkish nation as envisioned by the Young Turks.

In short, especially as the war was not going as hoped, the Young Turks needed to find someone to blame for their calamities, a scapegoat. And who better than this longtime “infidel” and “foreign” element right in their midst, the Armenians?

Red Sunday

April 24, 1915, known in history as “Red Sunday,” is to the Armenian Massacre (to some degree) as was November 9-10, 1938, Kristallnacht, was to the Nazi Holocaust a few decades later: a violent precursor to much more violence to come.

In response to the perceived threat to Turkey by the Armenians, exacerbated by those Armenians fighting alongside the Russians (not a position that, perhaps, even a majority of Armenians were sympathetic with), the Ottoman government ordered the deportation of numerous Armenian intellectuals on April 24, 1915.

The law itself, called the Tehcir Law, was from the Arabic word “deportation,” or officially known as the Relocation and Resettlement Law; it authorized the deportation of the Armenian population from the lands of the Ottoman Empire (or at least what was left of it).

The first wave of “deportations” consisted of the arrest of more than 200 Armenian intellectuals from Constantinople.These included clergy, physicians, editors, journalists, lawyers, teachers, and politicians. Eventually, the total number of arrests and deportations amounted to 2,345.These detainees, after having been moved around the empire, were almost all killed.

This was Red Sunday.

The Massacre Begins

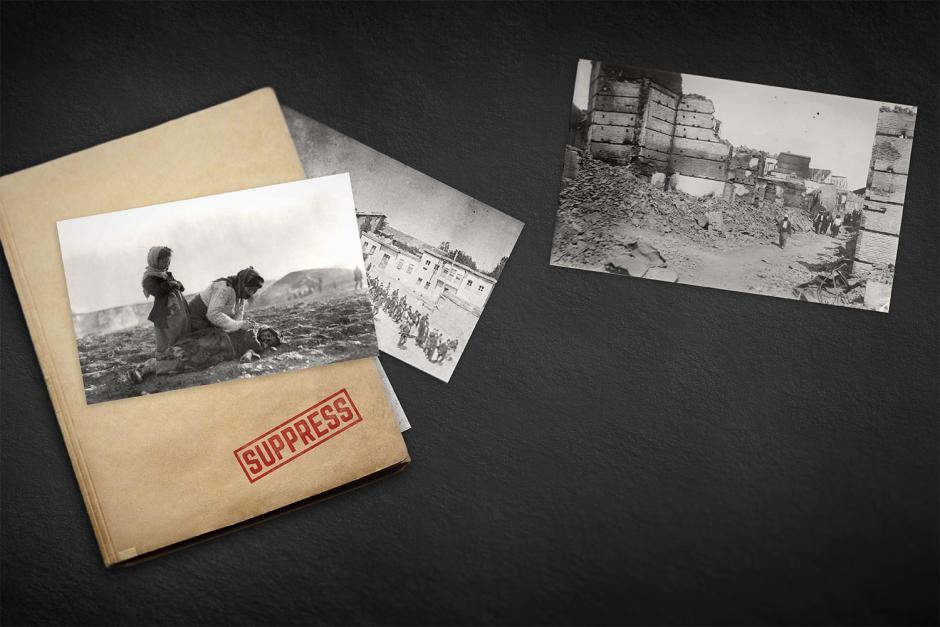

Red Sunday, however, was only the beginning. With the authority of the Tehcir Law, the state began what is known as the Armenian Massacre or, as it has been called (much to modern-day Turkey’s strenuous objections), the Armenian Genocide.

Orders went around the empire, instructing local governors to carry out “deportation” and “resettlement” of Armenians to Ottoman-controlled Syrian deserts. Those governors who refused (and some did) were replaced by more compliant bureaucrats. Despite the euphemistic language, many knew what was intended: the extermination of the Armenians. Indeed, the Young Turk, Taalat Pasha, one of the top leaders in Turkey, had made it clear that were he to get power, the extermination of the Armenians would be a priority.

It was. Between 1915 and 1916, Armenian men, women and children were driven from homes, schools and workplaces, their property being redistributed among the Turkish population itself. Much like what happened in the Holocaust, when entire areas were judenfrei (free of Jews), entire provinces were emptied of Armenians.In what sounded also frighteningly like the future SS Einsatzgruppen (Nazi troops whose main task was the murder of Jews), the Young Turks created a “Special Organization,” which created “killing squads” who carried out “the liquidation of the Christian elements.” These killing squads were often made up of murderers and other ex-convicts. They drowned people, beat them to death, crucified them, and burned them alive. Women were systematically raped and tortured before being killed.

One Turkish soldier later described what happened like this:

“Then the deportations started. The children were kept back at first. The government opened up a school for the grown-up children, and the American Consul of Trebizond instituted an asylum for the infants. When the first batches of Armenians arrived at Gumush-Khana all able-bodied men were sorted out with the excuse that they were going to be given work. The women and children were sent ahead under escort with the assurance by the Turkish authorities that their final destination was Mosul and that no harm would befall them. The men kept behind, were taken out of town in batches of 15 and 20, lined up on the edge of ditches prepared beforehand, shot and thrown into the ditches. Hundreds of men were shot every day in a similar manner. The women and children were attacked on their way by the (“Shotas”) the armed bands organized by the Turkish government, who attacked them and seized a certain number. After plundering and committing the most dastardly outrages on the women and children, they massacred them in cold blood. These attacks were a daily occurrence until every woman and child had been got rid of. The military escorts had strict orders not to interfere with the “Shotas.”

“The children that the government had taken in charge were also deported and massacred.

“The infants in the care of the American Consul of Trebizond were taken away with the pretext that they were going to be sent to Sivas, where an asylum had been prepared for them. They were taken out to sea in little boats. At some distance out they were stabbed to death, put in sacks and thrown into the sea. A few days later some of their little bodies were washed up on the shore at Trebizond.”

Though the Turks had hoped to perpetrate their crimes under the cover of war, stories leaked out and made the international press—the U.S. media in particular. Headlines ran like this: “Million Armenians Killed or In Exile.”“Armenians. Half a Million Killed. Blood-curdling Horrors.” “The Massacre of a Nation: All of the Horrors, Tortures and Barbarities of History Surpassed in List of Cruelties Practiced by Turks on Defenseless Armenians.”

It was during this time, too, that the phrase, “starving Armenians” entered the world lexicon.

What’s not well known now, amid the difficult politics in the present Middle East, was Kurdish involvement back then.Though today bitter enemies of the Turkish government, during this tragedy, various Kurdish tribes openly participated in the carnage; though some others worked very hard to help save as many Armenians as possible.Unlike the Turks even to this day, the Kurds have been very open about their complicity in the massacre, calling it a “genocide” and admitting their guilt.

Aftermath

After World War I ended, and the remains of the Ottoman Empire were carved up by the victors, a reckoning needed to take place for the atrocity, somewhat like what happened after World War II and the Nuremberg war crimes trials. Talaat Pasha, one of the three head Young Turks, and considered the mastermind behind the killings, was sentenced to death in absentia, along with others: but he had fled to Berlin.However, because of political pressure, and various agreements with the victors, most of the proceedings fell by the wayside.The new government of Turkey simply wanted to move on, and the allies seemed more than ready to let it. (Something similar also happened after World War II, when the Allies, eager for West German help in countering the new threat, the Soviet Union, had turned a blind eye to many lower-level functionaries.As it has been said: “After the war, the Russians killed their Nazi war criminals, while the Americans hired them to work for the CIA.”) The Allies did hold many war criminals accountable at the Nuremberg trials, but practical considerations did result in many scientists and others simply seconded to ongoing war efforts against Japan.

Maybe others were ready to move on, but many Armenians weren’t.In what sounds like a spy thriller, a group of Armenians, called the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, created a covert operation to seek revenge on the leaders of the massacre.Dubbed Operation Nemesis, between 1920 and 1922 these Armenians hunted down and killed a number of senior officials involved in genocide.The most sensational of those assassinations was that of Talaat Pasha, killed in broad daylight in Berlin, on March 15, 1921. He was shot dead in front of numerous eyewitnesses by an Armenian named Soghomon Tehlirian; a man who had watched as his family was massacred in 1915. Arrested on the spot, Tehlirian went on trial in Germany (he had wanted to get caught), and the proceedings helped bring to light the horror that happened. This was especially needful in Germany, which, as an ally to the Ottomans, hadn’t had much access to news about the atrocities. Tehlirian himself had been acquitted, and eventually he moved to the United States.

Lessons?

What about today, more than 100 years after the massacre? What have we learned? One could argue that with the Nazi Holocaust, with all its horrific parallels, following right on its heels—not much.What hasn’t helped matters is that, to this day, the Turkish government, while admitting the violence against the Armenians had taken place, refuses to call it a genocide, arguing that use of the term was a gross distortion of the truth, and that the deaths were just an unfortunate consequence of a war in which many different people groups suffered. It was not, they claim, a systematic attempt to exterminate the Armenians. Turkey’s most conciliatory step has come in some condolences offered in 2014 to descendants of genocide survivors by Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who was then prime minister and now the president.

In Turkey itself, Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code, which took effect in June 2005, makes it illegal “to insult Turkey, the Turkish nation, or Turkish government institutions.” It aims to silence any kind of valid criticism of state policies, official ideology, or history of Turkey.Thus, when anyone in Turkey tries to bring up what happened, they face the threat of jail.

Meanwhile, despite fierce objections from Turkey, about two dozen nations have formally acknowledged the reality of the genocide, with Germany finally doing it in 2016, an action that brought a harsh rebuke from its longtime ally, Turkey, which recalled its ambassador, arguing that the Germans did it to turn attention away from its own dark past.As of this writing, the United States—for a host of reasons, mostly political—still refuses to officially use the G word.

Unfortunately, despite the harsh lessons of the twentieth century, early events within the beginning of the twenty-first century don’t make it appear that those lessons have stuck.That part of the world, as others, remains a festering cauldron of religious, political, and ethnic tensions that more often than not have resulted in bloodshed. ISIS, the Syrian Civil War, the Shia-Sunni divide, have all shown how quickly ancient animosities, fueled by desire for a resurgence of the “glory” days of a mythical past, can quickly escalate into violence, especially when it’s so easy to forget how dangerous these ideals can be.

A recent example of how fast these things can be forgotten can be seen in American news and commentary program on the YouTube channel. Called the TYT Network, the show focuses on such issues as money in politics, drug policy, Social Security, the privatization of public services, climate change, and questions of sexual morality.The TYT Network takes a liberal position, with host Cenk Uygur asserting that the show is aimed at the “98 percent ‘not in power’” and at what he describes as the Americans who hold progressive views. All in all, it sounds pretty harmless.Except for one thing.What does TYT stand for?

The Young Turks.

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.