This Is Not My Father’s World

Charles Mills July/August 2020Frank Schaeffer is the son of Francis and Edith Schaeffer, who founded the L’Abri community in Switzerland in 1955. L’Abri was a hippie, Evangelical commune through which many a young seeker passed and where young Frank was raised according to what he calls the doctrine of fundamentalist Christianity. Dad was an evangelical Christian theologian, philosopher, and Presbyterian pastor who passed away in 1984. Dad was in many ways the guru and founder of the modern Evangelical Right movement in America.

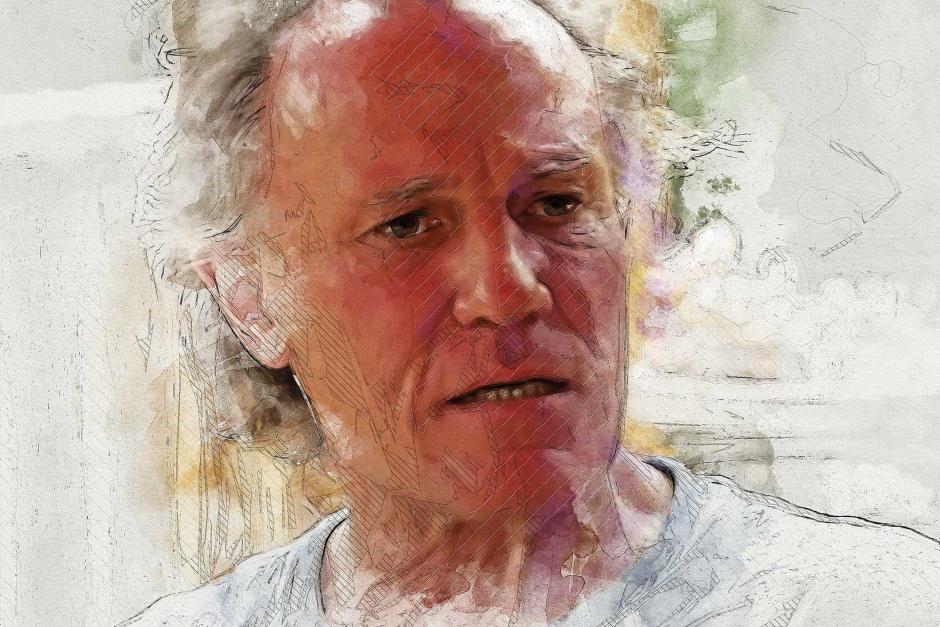

That was then. This is now. Something happened to Frank Schaeffer along the way, and he has become an outspoken critic of many of the religious and social issues he at one time fully supported. I recently had the privilege of talking on behalf of Liberty with the now-68-year-old author, film director, screen writer, and public speaker. My primary purpose was to discuss one of his books, Why I Am an Atheist Who Believes in God.

But our conversation took on a life of its own as we wandered freely through his life, revealing the deep insights and personal motivations that carried him on his journey from unquestioning faith to unwavering doubt. His experience pulls back the curtain on certain realities that are impacting religious liberty today. I believe we’d do well to seriously consider what he has to say.

LIBERTY: Frank, since you were there when much of it happened, what were the origins and goals of the so-called Religious Right when Jerry Falwell birthed it in 1979?

SCHAEFFER: If you’re referring to Jerry Falwell specifically, first let me say that I knew him well and spoke from his pulpit twice as a young, nepotistic sidekick to my father, Francis Schaeffer. That’s not an unusual phenomenon in the Evangelical world. A lot of God businesses turn into family businesses, sort of like the British royalty/North Korean version of passing the torch.

I found myself in my early 20s with audiences that were vast for someone that age. I was there, not because I’d earned it, but because my dad was having chemotherapy and wasn’t available. He was battling cancer at the time, so they’d get me instead. In the lingo of the Evangelical world, “the mantle had passed” to me, and “God’s hand was clearly on me.”

I’d spend time with people like Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and the rest of that group, doing things that, normally, people would have to be a bit older to get to do. This provided a kind of inside view of the formation of the Religious Right.

As for Jerry Falwell, he was a segregationist in the sixties and eventually latched onto the anti-abortion cause in the late 1970s. Like many Evangelicals at that time, he was pro-choice. W. A. Creswell, who was the president of the Southern Baptist Convention and pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas at that time, told us that he didn’t believe life began until a baby draws its first breath.

Billy Graham, the famous evangelist who often appeared on Dad’s platform, and Dr. C. Everett Coop, who would become Ronald Reagan’s surgeon general after we made a film series called Whatever Happened to the Human Race? helped mark the beginning of the Protestant Evangelical involvement in pro-life issues.

When you ask why and how this all formed, a lot of it had to do with fundraising. There was also White nationalism, the segregating of White schools, and the lashing out at federal and judicial rulings that went with it.

I think people like Jerry Falwell and James Dobson of Focus on the Family were always looking for “the next hot issue” with which to rev up their listeners, viewers, and supporters—to keep them on the edge of their seats and get them sending in that next $25 check so they could save America from the “fill in the blank”—feminists, gays, whoever or whatever it might be. That’s, honestly, how this all came about.

Now, when you get down to the rank and file to which we were all speaking, there were not only a lot of sincere believers and very good people among them, there were folks who were in it for the right reasons. They were trying to mirror what they believed to be the teachings of Jesus Christ. But, as it is today, when you got up into the level of the big-time leaders—for instance, Franklin Graham and others—it was a completely different deal. There’s always a calculation about what will work, where the money could be raised best, and so forth.

So two things were going on: a lot of sincere belief on one hand, and a leadership that was utterly corrupt to its core. That’s a thumbnail of how I see it as someone who was there from the beginning.

LIBERTY: What was the main event or motivation that moved you from behind that bully pulpit into areas you hadn’t ventured?

SCHAEFFER: The way I would put it may come off as a little odd; but it had more to do with aesthetics than morality.

I can remember thinking, as I was about to take the stage as the keynote speaker at the Southern Baptist Convention in front of some 23,000 pastors in the early 1980s, when my dad couldn’t make it, that I was heading into my late 20s and this was going to be the first day of the rest of my life. None of the folk to whom I was talking were the kind of people who liked the movies I liked, or were into the arts that I was into, or enjoyed the kind of music I enjoyed.

My cultural background—growing up in Europe as Francis Schaeffer’s son—really had very little to do with White, middle-class, American Right Wing Christianity of the Jerry Falwell brand. The only thing that brought Dad to their attention was his early books, such as The God Who Is There and Escape From Reason. Those books became best sellers before he got into politics. Then, later, there was the issue of abortion, which actually caught fire with the help of Dad, me, Dr. Koop, and others. It became a political issue that Ronald Reagan started utilizing when he switched from being pro-choice to being anti-abortion. There were many other issues tied to it.

I realized that all of this was going to doom me to move in those circles forever, and I frankly didn’t even like the guys at the head of the movement. It was all fakery to me! I couldn’t see myself spending the rest of my life promoting it.

The second reason was my marriage. I had been raised with the sort of domineering, Calvinistic, Evangelical thought that men should be in charge of everything. This made relationships worse. I was on the road six months a year, and when I’d come home, I’d always be angry with myself and with my family. I was in love with my wife. But it was no picnic realizing that the involvement with the kind of people I was spending time with, along with the strains it was putting on my own life as I was secretly wanting to go in different directions, was turning me into a world-class jerk.

Not liking who I was becoming in this circle, getting offered places on the boards of all these big ministries, and realizing that if I wasn’t careful, this was who I was going to be forever, I knew something had to give.

Then I started questioning the theology itself. Did I really believe this stuff? Did I really believe that we were correct on the politics concerning gay issues or feminist issues or access to abortion? As I started to look at the issues in and of themselves from outside of being part of the movement, it all began to disintegrate. By the time I wrote my memoirs Crazy for God, I was essentially signing my own death warrant for further involvement. There was no way back. I burned my bridges, and then tried to figure out where to go from there.

LIBERTY: Are you saying that the God you grew up with, the God you loved as a child, was not the same God you were walking with as you moved into these other areas?

SCHAEFFER: I don’t think I grew up loving any God. I think I grew up sitting and trying to get through hour-and-a-half-long Evangelical sermons and feigning interest. Eventually I looked at myself and said, “What’s wrong with me? Why don’t I feel more fire for this?”

What did fire me up in terms of my involvement in those issues was the fact that I loved my parents. They were good people. Dad was not a fake. He was not a thief. He was not of those other folk’s ilk. Comparing them to him, Dad worked on the edge of his bed in an old rocking chair with a tea tray. He didn’t even have a desk! We didn’t own a car. The first time I ever flew first class in my life was when we were out on the road and millionaires like Richard DeVos of Amway were footing the bill for our films. Dad and I were embarrassed by that sort of thing.

So, coming from this humble, little ministry which, no matter what you think of the theology, was authentic, and suddenly stumbling into the big-time of the God business of America, was a shock to my system from which I couldn’t recover.

I never learned to love the Evangelical American God. The God my parents served was a much more humble being. Mom and Dad were about reaching out in the open home environment of L’Abri, where people were camping out on the floor in sleeping bags. It was about my dad working in his bedroom, the fluke of his books becoming best sellers, and the documentaries I produced, directed, and distributed raising millions of dollars. My father’s ministry was a straightforward, evangelical ministry.

It was only during the last seven or eight years of his life that everything took a political spin. This spin helped shape the America we’re in now and laid the groundwork for Donald Trump to become president by turning the abortion issue into the litmus test upon which all other issues turned.

I wasn’t brought up in this environment. We crashed into it, and I rejected it.

LIBERTY: If your dad could talk to you now—if he could look around at your life and hear what you’re saying, see what you’re doing, and read what you’re writing—he’d be on board with it?

SCHAEFFER: He wouldn’t agree with a lot of things I’m saying in terms of my conclusions about the Bible. I don’t believe in the “inerrancy of Scripture,” as he’d put it. I don’t believe it’s literally true. I think there are huge chunks of mythology in it. But when it comes to analyzing whether you want to spend the rest of your life serving the kind of political Right Wing machine that Evangelicalism has become, he’d be thrilled that I jumped ship, and would’ve been horrified if I’d stayed on board.

I think my dad would slit his wrists if he came back and found that I was a new Ralph Reed, for instance, leading something like the National Prayer Breakfast with Donald Trump and trying to dress him up and make him look presentable. My father would’ve been horrified by that. So if the choice had been me going with the program as it developed, or me jumping out, clearly to anyone who reads his nonpolitical works, which were about philosophy, history, and all the rest, they’d see that Dad would not have, in any way, fit into this environment.

Look for Part 2 of this interview in the next issue of Liberty.

-------------------------

Charles Mills interviewed Frank Schaeffer as part of the programming for the Liberty magazine weekly radio program called Life Quest Liberty, usually featuring Liberty editor Lincoln Steed. Charles writes from Berkeley Springs, West Virginia.

Article Author: Charles Mills

Charles Mills, a media producer, is the host of "LifeQuest Liberty" radio program. He writes from Berkeley Springs, West Virginia.