Uncharted Territory: Abortion, History, and Constitutional Interpretation

Michael D. Peabody November/December 2022Every so often a Supreme Court case comes to define a cultural moment. This year’s abortion-rights decision, Dobbs v. Jackson, will likely go down in history as just such a case. What will be the ripple effects of this landmark constitutional decision?

Illustrations by Michael Glenwood

This summer the Supreme Court held in Dobbs v. Jackson that individual states can decide whether to permit or limit abortion within their borders. While politicians and the media have focused on the immediate, practical impact of this decision, there’s another question that deserves our serious attention. What are the longer-term consequences of the majority’s reasoning in the case, which shifts constitutional interpretation from substantive due process to strict originalism colored by “history and tradition”?

In short, the rationale in Dobbs is that the Supreme Court must be silent on abortion because it is not specifically referenced in the Constitution. As Justice Brett Kavanaugh said in his concurring opinion: “The issue before this Court . . . is not the policy or morality of abortion. The issue before this Court is what the Constitution says about abortion. The Constitution does not take sides on the issue of abortion.”

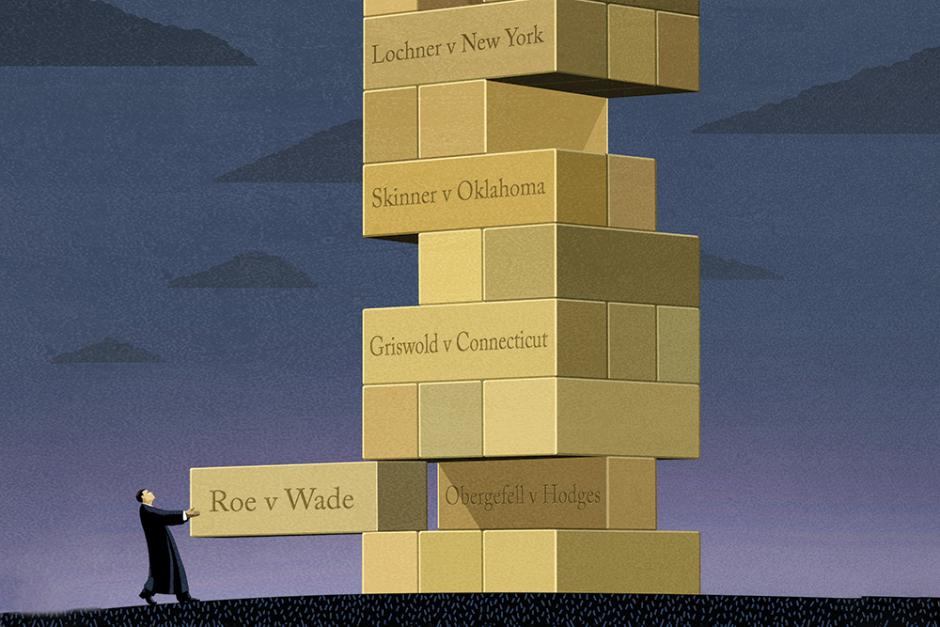

But the Constitution is also silent on a number of rights that the Supreme Court has determined to properly exist. Through the years the Court has found that people have freedoms not specifically mentioned in the Constitution—freedoms that states have, at various times, tried to take away. These include the right of workers to contract with employers (Lochner v. New York, 1925), the right to have children (Skinner v. Oklahoma, 1942), the right to use contraceptives as birth control (Griswold v. Connecticut, 1965), the right to interracial marriage (Loving v. Virginia, 1967), the right to freedom from excessive punitive damages (Gore v. BMW, 1996), and the right to same-sex marriage (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015).

In these decisions the Court overturned state laws by relying not on specifically granted constitutional rights but on general principles in the Constitution.

Substantive Due Process: A Complex Legal History

The exact definition of the substantive due process doctrine has been the subject of much debate. In simple terms, though, it says that a court is justified in bringing close scrutiny to bear on government actions that infringe on certain fundamental rights—even if these rights are not specifically spelled out in the Constitution.

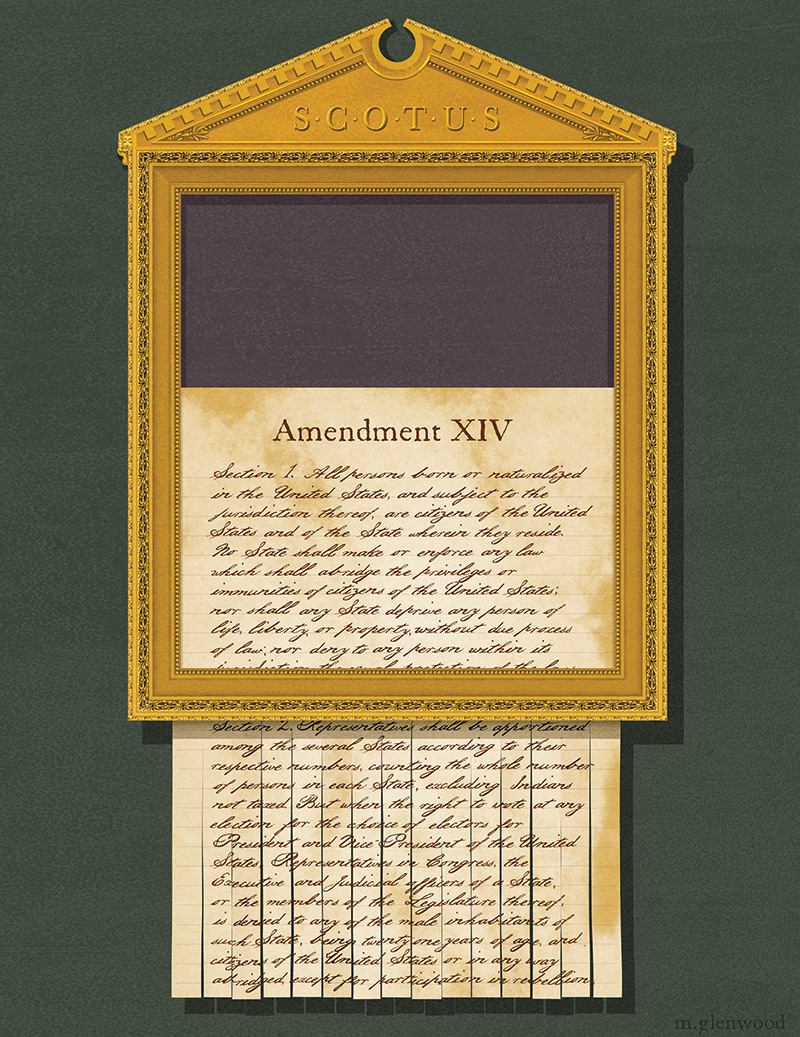

This doctrine stems from the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, which says, “No person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law.” While this was intended only to apply to actions of the federal government, in large part to allow for slavery, this changed after the Civil War. The states also had to agree to abide by this provision via the post–Civil War Fourteenth Amendment (1868), which explicitly applied to the states. The Supreme Court has since interpreted this to mean that states also must honor many other portions of the Bill of Rights. This is known as the “incorporation doctrine.”

Substantive due process has been much disputed because it embraces the idea that the original language of the Constitution itself is not set in stone and is not sufficient to provide for all the freedoms that people currently enjoy. Originalists, who adhere only to the specific language of the Constitution, argue that it can only be legitimately interpreted based on what its authors intended when it was written. Originalists argue that courts cannot add to the Constitution any rights, no matter how attractive, if these rights are not found within the 7,591 words of the document, including its amendments and signatures.

Originalists will claim they understand the “true meaning” of the Constitution and are therefore more objective. Yet their interpretation of what the authors intended to say is filtered through a subjective, broad-based view of “history and tradition.”

The Court in Dobbs could have merely taken a scalpel to Roe v. Wade by allowing, for instance, Mississippi’s 15-week-ban on abortion to stand or even deciding that the Fourteenth Amendment extended rights to the unborn. Instead, the Court threw a grenade into the heart of “substantive due process” and created a new precedent that embraces originalism. If a right is not explicitly listed in the Constitution or cannot be construed to be part of the “original intent,” it does not exist.

Justice Clarence Thomas issued a concurring opinion that makes the threat to substantive due process even more clear. He writes, “ ‘Substantive due process’ is an oxymoron that lacks any basis in the Constitution.” He laments that although Dobbs focuses on abortion, other Court-established rights should be revisited, including, among others, same-sex conduct and marriage, and contraception.

Originalism Versus History and Tradition

While parading a strict adherence to the specific language of the Constitution, the Court in Dobbs allows itself a massive exception called “history and tradition.” Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Alito says, “The inescapable conclusion is that a right to abortion is not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions. On the contrary, an unbroken tradition of prohibiting abortion on pain of criminal punishment persisted from the earliest days of common law until 1973.”

In combination, subjective “history and tradition” coupled with an ostensibly “objective” originalism can create unfortunate case law.

In what was arguably the worst Supreme Court decision of the 1800s, Chief Justice Roger Taney issued a decision in 1857 intended to declare forever that enslaved people were property, with no rights under the Constitution. Taney wrote that Dred Scott, who had sued for his freedom because his enslaver had transported him through a “free” state, had no right to sue. In fact, Taney wrote, Congress’s passage of the Missouri Compromise allowing for free states and slave states acted to deprive enslavers of their “liberty” and “property.” Thus, he claimed, the Missouri Compromise “could hardly be dignified with the name of due process of law.” Taney argued that a person who had slaves should be able to move freely between the states without losing that “property” right.

Relying on a claim to “history and tradition,” Taney wrote that “the legislation and histories of the times, and the language used in the Declaration of Independence, show, that neither the class of persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as part of the people, nor intended to be included in the general words used in that memorable instrument.”1

Even if the Founders may have felt personally opposed to slavery, they had created a document born of compromise. It gave states the power to decide whether to allow slavery within their borders but included language that, should an enslaved person escape, free states may have to return them to the “Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.”2

To be sure, this fugitive slave clause had some legal gaps that allowed “free” states significant judicial discretion in whether they would return escapees. But the Scott decision federalized slavery by requiring all states to return escapees to slaveholders. In short, the Underground Railroad now had to expand to Canada because escaping to Northern states was no longer sufficient.

Some scholars, including originalist Robert Bork, have argued that Taney’s approach to slavery was an early approach to “substantive due process.” Bork famously contended that “who says Roe must [also] say . . . Scott.”3

But it can also be argued that Taney’s approach arises from a hybrid of originalism and “history and tradition.” In claiming slavery was protected by the Constitution where no such language existed, Taney’s primary argument was that slavery had existed for hundreds of years and was not excluded by the Founders.

The Scott decision sent shock waves across the country and ultimately became a catalyst for the Civil War. During the years of Reconstruction after the Civil War, as a condition of rejoining the Union, Confederate states agreed to sign three new amendments to the Constitution: outlawing slavery (Thirteenth), applying the due process clause to the states (Fourteenth), and allowing formerly enslaved people to vote (Fifteenth).

Confederate states grudgingly signed on to these amendments, claiming they had little choice. Yet many of these rights remained ignored and neglected until, almost a century later, they gained new life through the civil rights movement of the 1950s to 1970s.

Griswold and Roe and the Right to Privacy

In 1965 the Supreme Court heard a case in which the state of Connecticut had prosecuted a director of Planned Parenthood, Estelle Griswold, for providing married couples with contraception in violation of an 1879 state Comstock Law banning birth control. The state argued that the law was necessary because it prevented extramarital sexual relations, presumably by punishing unwed couples with pregnancy.

The Court found that there is a “zone of privacy” in the bedroom free from state interference.

Most of the justices thought Connecticut’s Comstock Law was ridiculous, and even dissenting Justice Potter Stewart noted that the law was “uncommonly silly” and “obviously unenforceable.” But, hewing to a strict originalist approach, Stewart said that the Court should not come up with a new “right to privacy” on its own but should instead overturn the law based on a due process right found within the Fourteenth Amendment. Stewart also joined Justice Hugo Black’s dissent that, absent a specific right to privacy in the Constitution, the Court had no basis or jurisdiction for finding the state law unconstitutional.

The 1973 case Roe v. Wade built on Griswold to expand the right of privacy to the right to an abortion. In the decision Justice Harry Blackmun wrote that there was nothing in the Constitution, including the aforementioned fugitive slave clause, that expanded the rights of personhood to the unborn. Blackmun wrote, “We need not resolve the difficult question of when life begins. When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus, the judiciary, at this point in the development of man’s knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer.”4

The majority found that despite the lack of clear language in the Constitution that allowed for abortion, there was a “right to privacy” that allowed for abortion, just as it allowed for contraception.

What About Fetal Personhood?

Although Roe was based on the idea that there is a “right to privacy” that allows for abortion, there was no absolute right to abortion free from state intervention. Without a clear scientific basis, the Court decided on a trimester system that would allow a woman sole discretion to have an abortion in the first trimester, a state could regulate abortions in the interests of the mother’s health in the second trimester, and in the third trimester, the state could regulate or outlaw abortion unless it was necessary to preserve the life or health of the mother.

In Roe Blackmun addressed the argument raised by Texas and amici that the fetus might have Fourteenth Amendment rights. He wrote, “If this suggestion of personhood is established, the appellant’s case, of course, collapses, for the fetus’ right to life would then be guaranteed specifically by the [Fourteenth] Amendment.”

States have long treated fetuses who are candidates for birth very differently from candidates for abortion, even if there is no objective difference between them. Under Roe the rights of a fetus did not hinge on an overarching Fourteenth Amendment right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. At least during the first trimester they hinged, instead, on the pregnant woman’s decision as to what value that life may have.

For instance, the state of California will pay for abortions for unwanted babies, and it will also pay for prenatal care. California’s abortion law was written into the Penal Code in 1967 as an exception to the homicide law. This law begins with language defining murder as “the unlawful killing of a human being with malice aforethought.” Then it says that the very same act is not prohibited if performed by a physician to save the life of the woman or if the “act was solicited, aided, abetted, or consented to by the mother of the fetus.”5

Killing a fetus without consent will lead to a homicide charge, as in the 2003 case of Scott Peterson, who killed his wife, Laci, who was pregnant with son Conner. Both died, creating the “double homicide” “special circumstance” that led to Peterson initially being sentenced to death.

Another example is from Florida, where in 2014 John Andrew Welden was first charged with first-degree murder for killing his unborn child after tricking his pregnant girlfriend into taking abortion pills.

Although religion and philosophy might answer that a fetus becomes alive after it first moves (the so-called quickening) or takes its first breath of air using its mouth rather than the umbilical cord, the scientific definition is that life starts when sperm meets a cell leading to the formation of a fertilized ovum or zygote. “The time of fertilization represents the starting point in the life history, or ontogeny, of the individual.”6

Christopher Hitchens, an atheist, wrote in his book God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything: “As a materialist, I think it has been demonstrated that an embryo is a separate body and entity, and not merely (as some really used to argue) a growth on or in the female body. . . . The words ‘unborn child,’ even when used in a politicized manner, describe a material reality.”7

The Dobbs decision, however, sidestepped this issue of fetal personhood. It did not establish that the fetus is, in fact, a person with constitutional rights, but instead threw the issue of abortion to the states.

What Next?

Some states will develop their own substantive due process rules. Some states may expand abortion rights to new extremes, discounting any legal interest in the value of prenatal human life.

Other states will move in the other direction. Some may find new ways to impose restrictions, such as electronically tracking women who travel to another state for an abortion.8 Some women may be forced to carry to term undeveloped fetuses who have died in utero. Pregnant children who are, by definition, rape victims may be forced to carry their babies to term, and a host of other issues may arise in the coming years that are not even contemplated now.

On the other end of life, assisted suicide and emerging discussions on euthanasia, along with rising costs of health care, mean that society’s understanding of the value and meaning of human life are changing. Thus, settling the question of whether a fetus is a human being may not provide the open-and-shut argument against abortion that people once thought.

So what do to? It’s easy to tell someone that they must “bear the consequence of their actions.” But what does this mean in practice? Should the male responsible for an unwanted pregnancy be prosecuted? Should promiscuous teenagers be dragged before magistrates? Should society incarcerate those who attempt to have an abortion and restrain them until they give birth in a prison hospital?

In a perfect world I would be able to wrap up this article with a clear conclusion and make a strong argument for or against Dobbs and plant a battle flag. But the reality is, I can’t.

Everything about the subject of abortion is complex and messy. It’s an issue with which the Roe Court clearly struggled. And we cannot expect the courts and legislatures today to fix it. Once the dust settles from Dobbs, society will need to figure out how to handle the issues that arise. I would propose that the quest for a workable solution will need to start with a society that protects the vulnerable, cares for the pregnant, the newborns, and for children. Advocates on all sides of the issue will need to stop judging from the sidelines and get involved in providing for the health of all involved.

Unmapped Legal Terrain

Beyond the issue of abortion, perhaps the most significant consequence of Dobbs is the new form of jurisprudence it has created. It’s an approach based on a hybrid of allegedly objective originalism and coupled with the subjectivism of “history and tradition.”

When drafted, the Constitution was intended to protect people from an overbearing government while at the same time protecting the ability of states to enslave people. It took a Civil War, and the post-War amendments, to require states to recognize that all human beings had federally guaranteed rights. The approach that Dobbs takes, rolling back the applicability of substantive due process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment, may allow almost any state-level restriction on unlisted freedoms to be upheld against a narrowing interpretation of the Bill of Rights.

For those who would argue for the human rights of the unborn, Dobbs made those rights more tenuous, as they are now subject to individual state laws. For those who argue that this is a human rights issue for the pregnant woman, this also leaves it up to the states. State restrictions, no matter how unreasonable or onerous, will be upheld by the Court, which will now take a hands-off approach for the foreseeable future.

In short, the approach seen in Dobbs has the potential to undo decades of civil rights advances, as courts apply a strict formalism to rights and chip away at hard-won freedoms.

1 Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857).

2 Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3, repealed by the Thirteenth Amendment.

3 R. H. Bork, The Tempting of America (United Kingdom: Free Press, 2009), p. 32.

4 Roe v. Wade, 410 U. S. 113 (1973).

5 P.C. section 187.

6 Bruce M. Carlson, Patten’s Foundations of Embryology, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996), p. 3.

7 C. Hitchens, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2008), p. 220.

8 Proposed Oklahoma law—SB 1167—would reportedly create a government-run database that would track pregnant people looking into abortion.

Article Author: Michael D. Peabody

Michael D. Peabody is an attorney in Los Angeles, California. He has practiced in the fields of workers compensation and employment law, including workplace discrimination and wrongful termination. He is a frequent contributor to Liberty magazine and editsReligiousLiberty.TV, an independent website dedicated to celebrating liberty of conscience. Mr. Peabody is a favorite guest on Liberty’s weekly radio show, “Lifequest Liberty.”