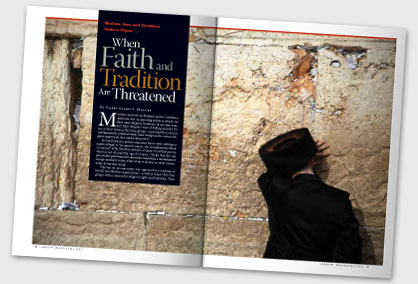

When Faith and Tradition Are Threatened

Allen Maller March/April 2012

Muslims and Jews in Holland and in California united in 2011 in opposing political attacks on their joint religious traditions of circumcision, and their religious ways of killing animals for use as food. Several Christian groups, concerned that secular and humanistic political values were being used to coerce religious expression, also joined the protest.

In San Francisco anticircumcision forces were seeking to make it illegal to “circumcise, excise, cut, or mutilate the whole or any part of the foreskin, testicles, or penis of another person who has not attained the age of 18 years.” Under that law any person who performed circumcisions would face a misdemeanor charge and have to pay a fine of up to $1,000, or serve a maximum of one year in jail.

The ban on circumcisions was opposed by a coalition of Jewish and Muslim organizations, as well as many Christian groups with a concern for religious rights and toleration. They were victorious when a superior court judge ruled in July that the measure to criminalize circumcision must be withdrawn from the November ballot because it would violate a California law that makes regulating medical procedures a state—not a city—matter. The judge then ordered San Francisco’s election director to remove the measure from city ballots.

In Holland a bill that will effectively ban the traditional religious way that both Muslims and Jews slaughter animals—a bill sponsored by the Party for the Animals—was approved in the Dutch lower house, where it was backed by the anti-Islamic Freedom Party, and opposed only by Christian parties that took a stand in defense of religious freedom. In January 2012 it was to go to the upper house of the Dutch parliament, where most observers expected it to become law.

Ritually slaughtered lamb is delivered at a halal butcher shop in The Hague, Netherlands,

Ritually slaughtered lamb is delivered at a halal butcher shop in The Hague, Netherlands,

Positions on religious slaughter vary around the world—in the United States, for instance, it is specifically defined as a humane method in the Humane Slaughter Act (1958)—but elsewhere several countries have already restricted or banned slaughtering unstunned animals.

The stunning of livestock was introduced in England in 1929 with the introduction of mechanically operated humane stunner devices. Stunning has been mandatory in the European Union since 1979, but member states can grant exemptions for religious slaughter. Stunning enables abattoirs to process animals more quickly at a lower cost. However, mis-stuns involving captive bolt occur “relatively frequently,” according to a 2004 European Food Safety Authority (Efsa) report; a mis-stun leaves the animal conscious and in pain. Animals can also regain consciousness after being stunned.

Animal rights groups see the Dutch bill as a stepping-stone toward further bans on religious slaughter. “The Netherlands is a very important example, but for us it’s just a battle, not the war,” says Dr. Michel Courat of Eurogroup for Animals, a federation of animal protection groups. “We need to win lots of other battles after this one to make sure more countries stop this practice.”

If the Dutch bill becomes law, Jewish and Muslim leaders say they will fight it in the European Court of Human Rights, arguing that it is a violation of the right to freedom of religion. “If the Party for Animals proposed a law that said there shouldn’t be any slaughtering of animals anymore, and everyone should be vegetarian, I could understand it better,” says Rabbi Benjamin Jacobs. “But it’s a vote against religion.”

A Dutch Muslim umbrella group, the Contact Body for Muslims and the Government (CMO), accused the Party for Animals of leading an “emotional” campaign based on misleading information that “wrongly created the impression that Muslim and Jewish methods of slaughter are barbaric and outdated.”

“We’re afraid that other countries in Western Europe will follow the Dutch example,” says CMO chair Yusuf Altuntas. Jewish and Muslim leaders see a worrying global trend, with the Netherlands a critical test case. They are fighting a battle on two fronts—to dispel the idea that there is anything inhumane about their traditional methods of slaughter, and to defend their right to live according to their religious beliefs.

Both faiths put great emphasis on animal welfare, and adhere to a one-cut method of slaughter intended to ensure the animal’s rapid death. Under Jewish and Islamic law, animals for slaughter must be healthy and uninjured at the time of death, which rules out driving a bolt into the brain—though some Muslim authorities accept forms of stunning that can be guaranteed not to kill the animal. Under Orthodox Jewish law, or shechita, the animal’s neck is cut with a surgically sharp knife, severing its major arteries, causing a massive drop in blood pressure, followed by death from loss of blood. Supporters say unconsciousness comes instantaneously—the cut itself stunning the animal. A similar procedure is used in Islamic slaughter, or dhabiha. Both Islam and Judaism stress that diet should not just be about calories. A religious diet is an exercise in spiritual discipline and in God consciousness. We do not eat only to “fuel up” like a machine. Nor should we eat only to enjoy ourselves.

From the Jewish point of view, God has given us a diet that is good for us physically and spiritually. That diet is found in the Bible, in the later Jewish writings, and in the Koran. Non-Jews can also gain many benefits from following most or all of this diet. Like all diets, a kosher holy diet must be followed daily to be effective. Like all diets, you should not become a fanatic in following this diet. Moral issues are more important than any one particular part of the diet. Thus, as a Reform rabbi, I would say that honoring a parent while visiting at home is more important than strict observance of a kosher diet. Nevertheless, like all diets, and all forms of spiritual exercise and meditation, the more frequently you fail to keep your kosher holy diet, the less you will benefit from it.

Food is the most important single element of animal life. But unlike all other animals, humans do not live by bread alone. The act of eating is invested with psychological and spiritual meanings. The Torah asserts that we should “Eat; become satiated/satisfied; and bless the Lord” (see Deuteronomy 8:10). This is how I, as a Reform rabbi, interpret these words:

Eat! Humans, like all animals, need to eat in order to live, but unlike all other animals, some humans will not eat certain foods that other humans will gladly eat. This universal human trait proves that “humans do not live by bread alone, but humans may live on anything that God decrees” (see Deuteronomy 8:3). Thus by periodically not eating at all (fasting), Jews, Muslims, and Christians live by God’s words. But some people reject the enjoyment of eating and add extra days of fasting to their diet. Other people carry vegetarianism further, and stop eating all egg and milk products. The Torah commands a moderate path between simply killing and eating anything you want and excessive fasting and/or rejecting broad categories of food, such as vegetarians and vegans do.

Become Satiated/Satisfied! If we eat only foods that we enjoy, we end up with a physically unhealthy diet. Obesity accounted for almost 26,000 deaths in the year 2000, and it has gotten worse each year. Our natural tastes do not lead us to good health. Maximizing enjoyment in the short run leads to disaster in the long run. Self-discipline leads to longer life. Religious self-discipline leads to a higher spiritual life. If you eat your fill, you will become satiated. If you eat according to God’s decrees, you will become satisfied.

Bless: The Sages rule that we should say a blessing even if we eat only a small piece of bread the size of an olive. If that is all you have, be grateful you have that. One person can be satiated and not be satisfied, while another can be satisfied yet not satiated. “Who is wealthy? Those who are satisfied with what they have” (Avot 4:1). The blessing after the meal is a mitzvah from the Torah. The Sages also ruled that we should say a blessing—the motzi—before we eat. The motzi ends with “who brings forth bread from the earth.” This phrase from Psalm 104:14 is preceded by “who makes the grass spring up for cattle,” to remind us every time we eat that we are part of the animal world and need to be considerate of their needs too. Thus it is a mitzvah not to eat until one’s animals have been fed (see Deuteronomy 11:15).

The Lord: We should also thank the cook, the baker, the miller, the farmer, and everyone else involved in producing our food. But the four fundamental elements for producing food are sun, rain, earth, and seed, none of which we create. Usually we are so caught up in using the end products that we forget our dependence on the fundamentals. That is why we so blithely harm our environment. We must remember what life is really based on, and why we should be both grateful and reverent to God.