Why RFRA?

Mitchell A. Tyner July/August 2015Is this Religious Freedom Restoration Act really that significant? Will it make that big a difference? Every time you lawyers start to explain what it’s all about, you lose me in your legalese.” The question came from a friend who supports religious liberty but has become dubious of the sometimes sensational rhetoric of its defenders.

How’s this for significant? Congress reversed the effect of a U.S. Supreme Court decision (it doesn’t do that very often) and for the first time did so because of a decision that reduced religious freedom. It took a three-year campaign by a coalition of religious and civil rights groups, including everybody from Jerry Falwell to the ACLU, to get the job done!

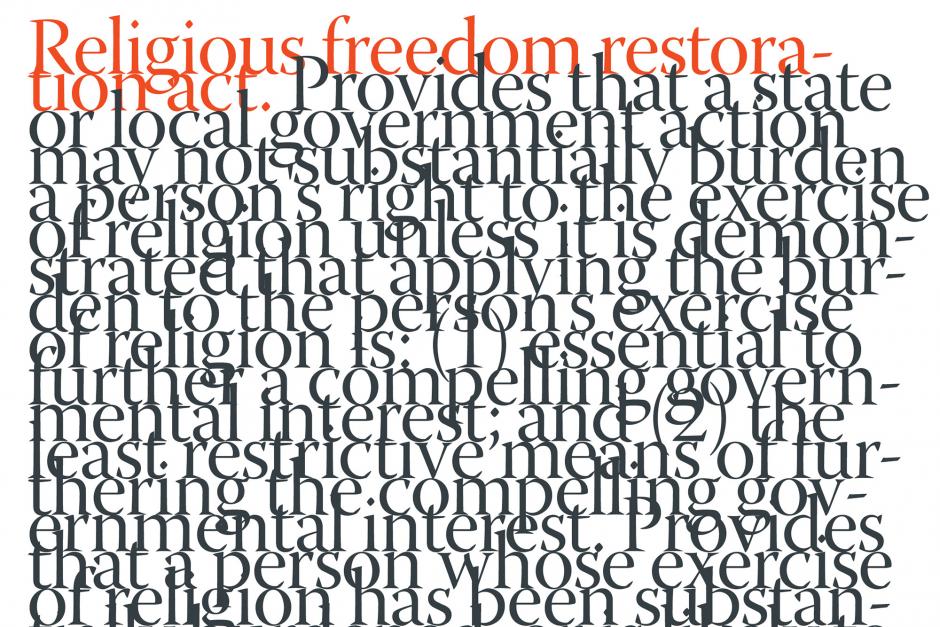

Unfortunately, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) is so technical that it’s hard to explain without a lot of legalese. But the answer to her other question is yes, it will make a difference!

If a Seventh-day Adventist applies to take a master plumber examination given only on Saturday, his Sabbath, he can require the state agency involved to prove that it would be a major hardship for it to give the exam on another day. Before RFRA, he could not do that.

If a prisoner, for religious reasons, avoids certain foods, he can now require the state to either give him an alternative diet or show why it can’t. Before RFRA, his case would have been addressed under a standard that gave all the advantage to the state and none to him.1

If a teenager is killed in an automobile wreck, his parents can protest, on religious grounds, the state’s right to force an autopsy. In one such instance before RFRA, a federal judge told the parents that although he personally considered the autopsy unjust, he was required to deny their claim.2

Yes, RFRA will make a difference in these and countless other situations. To understand why, you have to get a bit technical.

The U.S. Supreme Court establishes not only the meaning of the Constitution but also the rules under which it approaches cases involving constitutional provisions. Over the years the Court has decided that in claims involving governmental actions that burden fundamental freedoms, government should be required to justify its action by a high standard of proof.3 Such cases are said to be given “strict scrutiny,” meaning that government must show that its action was necessitated by a “compelling public interest” that couldn’t be met by any “less-intrusive means.”4 Other cases, involving lesser claims, are reviewed under a much more lenient standard: the challenged action will be upheld if it bears a “rational relationship” to a “legitimate governmental interest.”5 Because a modern government is assumed to have a legitimate interest in practically anything, government usually wins under that test. Obviously, the test applied by the Court may by itself determine the outcome of the case.

Which test is applied to cases involving religious freedoms? For the past several decades it has been that of “strict scrutiny.” When that happened, government didn’t often win. But in 1990 the Supreme Court ruled, in Employment Division v. Smith,6 that strict scrutiny would be applied only if the challenged action was intended to burden religion or was an application for exemption in a situation where exemption could be granted for a variety of reasons. If government unintentionally makes the practice of your religion more difficult and doesn’t allow any exceptions, you lose.

Put another way, the Court said that no religious exemption was constitutionally mandated from laws that are facially neutral and generally applicable. Unfortunately, some of the worst episodes of religious persecution in American history involved just that type of law. Minersville School District v. Gobitis7 involved Jehovah’s Witnesses’ objection to a facially neutral, generally applicable law requiring all public school students to salute the flag. The Supreme Court’s ruling that no religious exemption was required set off a nationwide outburst of violence against Jehovah’s Witnesses. It was also the precedent relied on by Justice Antonin Scalia, who wrote the majority opinion, to justify the Court’s rationale in Smith. Curiously, Justice Scalia neglected to mention that Gobitis was overruled just three years later in West Virginia v. Barnette.8

Smith was not followed by the physical violence that followed Gobitis, but violence to religious freedom has been done in dozens of cases in which courts were forced to follow the Supreme Court precedent. One example: Minnesota v. Hershberger9 involved a law requiring slow-moving vehicles to display a bright-orange triangle. The Amish protested that their religious belief forbade the use of bright colors, but offered to use a silver reflector that was just as visible as the orange marker. Lower courts applied the strict scrutiny standard and found that while a compelling public interest in highway safety justified the requirement that Amish buggies have safety markers, the silver reflector was a less-intrusive alternative that the state must allow. The Supreme Court sent that ruling back for reconsideration in light of Smith. Minnesota could give relief to the Amish, but was not constitutionally required to do so.

Justice Scalia, in Smith, advised religious groups to look to the legislature for further protection, and that’s exactly what they did. The result of their effort was passage of the RFRA, signed into law by President Bill Clinton on November 16, 1993.

RFRA restores the protection of religious freedom to its pre-Smith position. It may do even more. In several cases before Smith, the Court declined to apply strict scrutiny to religious claims, specifically those involving prisoners10 and members of the military.11 It has used such superlatives as paramount and gravest, explaining that use of such interests to burden religion must involve “only the gravest abuses, endangering paramount interests.”12

In the litigation that spawned, some defendant will almost surely challenge the constitutionality of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Did Congress have the authority to remedy what it perceived to be a judicial blunder?

The source of congressional authority for RFRA Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which gives Congress the power to “enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” The scope of Section 5 power was articulated a century ago in Ex Parte Viriginia:13 “Whatever legislation is appropriate, that is adapted to carry out the objects the amendments have in view, whatever tends to enforce submission to the prohibitions they contain, and to secure to all persons the enjoyment of civil and equal protection of the laws against State denial or invasion, if not prohibited, is brought within the domain of congressional power.”

That ruling was used by the Court in South Carolina v. Katzenbach14 to uphold Congress’s enforcement power under the Fourteenth Amendment. In that case the Court upheld a ban of literacy tests under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, even though the Court had held that such testing did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. Because the power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment includes the power to enforce the First Amendment, Congress arguably had full authority to enact the RFRA. That Congress may provide statutory protection for constitutional rights that the Court is unwilling to protect on its own authority was affirmed by the Court as recently as 1990.15

There could, however, be a catch note that Ex Parte Virginia gave Congress authority to enforce constitutional freedoms unless prohibited by some other constitutional provision. Perhaps the only serious challenge to the act would be a reading of the establishment clause broad enough to characterize the RFRA as an unacceptable effort by government to aid religion.

In late 1993 the Court granted review to a group of cases that invite it to reconsider the meaning of the antiestablishment provision of the First Amendment.16 The Court will hear those cases in early 1994, and could use them to alter or reject outright the understanding of that clause in use since Lemon v. Kurtzman.17 Yet even if a new analytic framework is adopted, the recent direction of the Court has been to widen the scope of acceptable governmental aid to religion. Therefore an establishment clause challenge to the RFRA is unlikely to succeed.

The act has made governmental efforts to resist accommodating religious conduct vastly more difficult. Defenders of religious freedom have been given a fine new tool. The results will in all likelihood be salutary. Yet Smith is still the law of the land. The RFRA does not reverse Smith; that is beyond the power of Congress. The act merely establishes a new right of action.

The RFRA may also make the reversal of Smith even more difficult. Courts will base a decision on constitutional guarantees only if no statutory protection is available. Thus even if a plaintiff files an action under both the RFRA and the free exercise clause, a court will reach the constitutional argument only if the RFRA does not offer the desired relief. And if the religious claim does not prevail under the RFRA, it will not under the free exercise clause using strict scrutiny or any other imaginable standard either. Thus the act may eliminate the practical possibility of reversing Smith.

Yet that problem too might be avoided if the RFRA is amended. Imagine that because of the increased volume of such litigation, the act is amended so as not to apply to prisoners’ rights. Lawyers representing prisoners would then base claims on the free exercise clause and invite the Court, after a change in personnel indicates the possible success of such an appeal, to revisit and reconsider Smith. Such a scenario, of course, is speculative. Though she still doesn’t understand all the technicalities, my friend now understands this: the Religious Freedom Restoration Act has restored necessary protection to the keystone in the arch of human freedoms.

1 Shabazz v. O’Lone, 482 U.S. 342 (1987).

2 Yang v. Struner, 750 F. Supp. 558 (D.R.I. 1990).

3 Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

4 Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963).

5 REA v. New York, 336 U.S. 106 (1949).

6 494 U.S. 872 (1990).

7 310 U.S. 586 (1940).

8 319 U.S. 624 (1943).

9 494 U.S. 901 (1990).

10 Shabazz v. O’Lone, 482 U.S. 342 (1987).

11 Goldman v. Weinberger, 475 U.S. 503 (1986).

12 Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 1526 (1972).

13 100 U.S. 339; 345, 346 (1880).

14 383 U.S. 301 (1966).

15 Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC, 497 U.S. 547 (1990).

16 Board of Education of Kiryas v. Joel Grumat, Docket No. 93-517; Board of Education of Monroe-Woodbury v. Grumat, Docket No. 93-527; New York v. Grumat, Docket 93-539.

17 403 D.S. 602 (1971).