Wired for Tyranny?

Jason Thacker September/October 2021In the West we often take technology for granted. We grow frustrated when the internet at home or the office goes down, even if only for a few moments. We grow impatient when we can’t quickly find what we are looking for online. We become outraged when technology companies seem to routinely misapply their content moderation policies. We speak out defiantly for all to hear on social media when we think our freedoms are being curtailed. We expect our elected officials to stand firm in the face of immense pressure for unfettered efficiency in order to safeguard our digital privacy and freedoms, even as we regularly and freely post intimate details about ourselves online for the world to see.

As members of a democracy, we have grown accustomed to having a say in how our society is structured and how it should be governed. We rightly believe that our leaders should be held accountable, and that government does not have unlimited power over us as individuals or our communities. We believe the government is designed and ordained by God to protect our natural rights and freedoms (Romans 13:1). And we may even expect the technology industry to uphold similar values given the influence of Western values, the intensity of market pressure, and the calls for public accountability. Regardless of where these companies operate around the world, we may presume they will uphold basic human rights even if there is little consensus on these matters, especially within the oppressive of authoritarian regimes.

But for all the challenges we experience in the West, we often fail to understand or even acknowledge the perils of technology on the international stage. The accountability and trust we have grown accustomed to in our society are often nowhere to be seen in many countries, where the rights and opportunities we cherish are completely out of reach for millions upon millions of people created in God’s image. Our lack of knowledge, understanding, and advocacy on the international stage may simply be because we have failed to grasp the extent of suffering around the world, or allowed this reality to penetrate our comfortable lives. Or maybe we have grown too accustomed to our Western understanding of human rights, technology, and the tenets of liberal democracy, and falsely assume that these are fairly normative across the world.

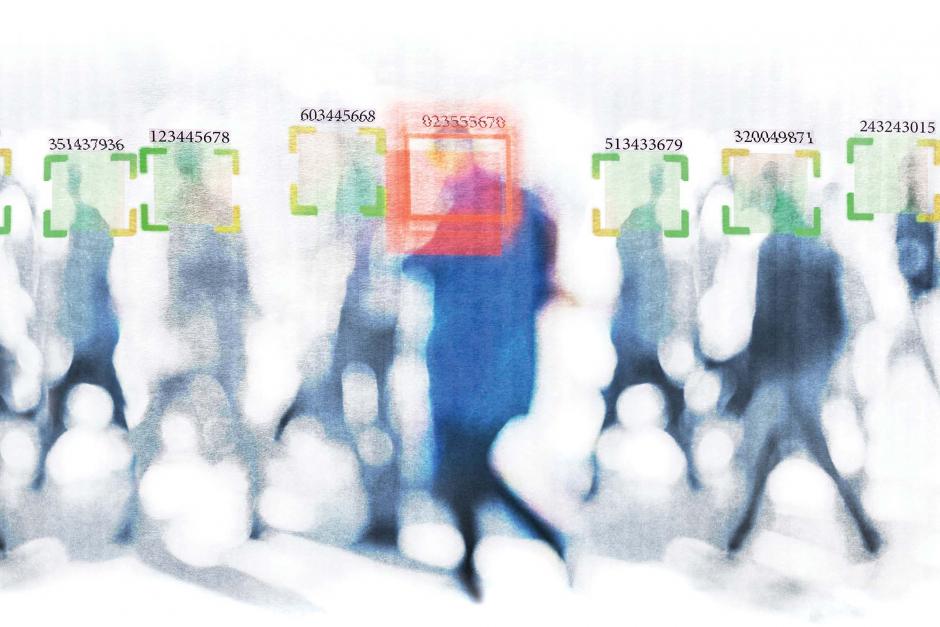

While technology is sometimes abused in the West, we still enjoy many of its democratizing effects. This reality, however, is just a dream for the many millions of people globally who live under repressive regimes ruled by authoritarian leaders. Today’s authoritarian regimes are empowered not only by the authority of the state through political power and military might, but also through the use of incredibly powerful tools such as the internet, social media, facial recognition systems, and other forms of mass surveillance.

The Goal of Authoritarianism

Digital authoritarianism, also known as techno-authoritarianism, is the way many leaders around the world wield the power of the internet and various forms of technology in order to gain or solidify control over their people. As a group of researchers recently wrote: “The same technologies that connect people and enable a free exchange of ideas, for example, are being used by authoritarians to deepen their grip internally, undermine basic human rights, spread illiberal practices beyond their borders, and erode public trust in open societies.”1 The same technology that was initially thought to be a democratizing force for good around the world—enabling anyone with access to communicate and share ideas—is now being exploited by the powerful few in authoritarian regimes to suppress the voice of the people, control and restrict access to information, and to stamp out any dissent that may challenge those in power.

An authoritarian government is often characterized by a central figure or political party that amasses enough power and influence to effectively strip citizens of certain rights and freedoms (although, unlike a totalitarian regime, it does not control every aspect of their lives). Authoritarian leaders usually seek to centralize their power on the political processes of a nation and the individual freedoms of the people. This is all normally done without any real type of constitutional accountability or oversight. And with the power and influence of technology, this centralization has become even easier.

This lust for power and push for centralization by authoritarian leaders are not new phenomena, nor are they reliant on recent advances in technology. For generations, powerful figures have embraced various technological innovations to push agendas and maintain dominance over others. According to Jacques Ellul, the late French sociologist and philosopher of technology, in his pioneering work The Technological Society, the state has routinely used technology to control the public narrative and shape the worldviews of its people. He explains, “The state has always exploited techniques to a greater or lesser degree.”2 For Ellul the term technique was more encompassing than our use of the word technology in English today. He saw technique as more than a simple tool or machine; to him it was part of a larger social force that could shape an entire society and culture. He described how the state, throughout human history, has regularly exploited military, financial, and communication techniques.3

One of the most horrifying historical examples of the authoritarian use of technology is revealed by Adolf Hitler in his insidious work Mein Kampf. Hitler and his Nazi regime were masters of propaganda. They used the latest technological advances of their day to wield significant power over much of Europe, pushing narratives about the “inferiority” of minority groups such as the Jewish people, and allowing the Nazi Party to deeply influence German people toward evil ends. But today’s authoritarian regimes have a distinct advantage over past generations. In our connected world the potential reach and power of these regimes has exponentially expanded with the rise of social media and internet-based communication.

Ellul rightly saw that “the conjunction of the state and technique is not a neutral fact,” meaning that technology has always altered how we perceive the world around us and our interactions with others.4 He says technology can be used by the state to “enable it to restore order, to guarantee certain liberties, and even perhaps to master its political destiny.”5 While the state may abuse these tools—as we see happening today in China and other authoritarian states, such as Iran, Belarus, and Russia—technology can also be used for good purposes once its power is widely recognized and proper controls are put into place. The state’s adoption of technology, then, is not merely about the isolated use of certain tools but how these tools can be used to amass power and control, and then wielded to exploit citizens and undermine human dignity.

Technologies of Control

Today we see the influence of digital authoritarianism growing throughout much of the world, including China, where the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has obtained near dominance over its people. The CCP controls access to information and deploys mass surveillance technologies such as facial recognition. It also maintains almost complete access to personal and institutional data collected by Chinese technology companies or those who seek to access China’s lucrative markets. The Chinese government has proudly and publicly promoted its use of these powerful tools for the watching world. For example, in 2017 the British Broadcasting Corporation reported that in the city of Guiyang the CCP had deployed one of the most complex and powerful facial recognition systems in the world made up of thousands of cameras, even including mobile units used by police.6 While it trumpeted this vast network for the world to see, the CCP was also using these same facial recognition systems in other regions in large part to identify, track, and detain various people groups within China. These same tools have been used to surveil various religious minorities in China as well, such as the Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang.7

The CCP has also built a robust and nearly impenetrable hold over public access to information. With “Chinanet” the CCP has essentially created a walled garden, where any information that could challenge the heavy hand of the regime’s control is filtered out completely. For example, the ability to search for any type of pro-democracy media, or even information about the infamous Tiananmen Square massacre, has been completely stripped from the Internet in China. This top-down approach to internet access and infrastructure has been mimicked around the world in countries such as Iran and Belarus.

China expert Elizabeth Economy describes how Chinese president Xi Jinping routinely paints a picture for his people of the West’s free access to the internet as “anathema to the values of the Chinese government.”8 She further describes how the Chinese leadership has “directed significant time and energy in investing in technological upgrades to increase the state’s already potent capacity to monitor and prevent undesirable content from entering and circulating through the country.”9 This level of control and amassing of power is less about “Chinese values” and is focused primarily on maintaining total control over the Chinese people by denying them access to information and barring their use of various communication tools. They are effectively prevented from shifting the power imbalance or seeking to hold their leaders accountable for their denial of basic human rights, such as religious freedom.

But these levers of control and power are not limited to the Chinese state. Other countries, such as Iran and Belarus, have taken note of the CCP’s tactics and in recent years sought to shut off the internet to their entire country in order to suppress dissidents—often on the heels of a fraudulent election or widespread cultural uprising. In August of 2020 President Alexander Lukashenko “won” another landslide victory, claiming an implausible 80 percent of the vote. Then in response to growing divisions in the country over the fraudulent election, Lukashenko reportedly instituted a nationwide Internet blackout, barring communication both internally among dissidents and externally to the watching world.10 Similarly in November 2019 the Iranian regime halted all communications in and outside the country in hopes of quelling protests in the country over rising fuel costs implemented by Tehran over U.S. sanctions.11 As new forms of technology are developed and made available to all, digital authoritarians will continue to use these powerful tools—such as deepfake videos and audio—to control the narratives their people hear or experience, as well as bend truth in other propagandistic ways.

Researchers Kendall-Taylor, Lindstaedt, and Frantz write that, ultimately, authoritarian use of technology “may also erode the traditions of tolerance that underpin democracy,” because such use alters perceptions of truth, accountability, and trust.12 As digital authoritarianism spreads globally, being aware of this danger is the first step in allowing us to push back against these power grabs, to stand up for the vulnerable, seek justice for the oppressed, and hold authoritarian regimes accountable for their dehumanizing methods of control.

How Can We Respond?

In our digitally connected environment we have access to more information than we can even begin to process, an overload that for many of us can spawn a lack of empathy for those suffering around the world. As writer Alan Jacobs puts it: “Navigating daily life in the Internet age is a lot like doing battlefield triage.”13 It is far too easy for those of us who live under the relative freedoms of democratic systems to read about these human rights abuses in authoritarian regimes and quickly forget as we continue to scroll through our social media feeds. But the call of Christians in this digital age is not just to acknowledge the existence of these abuses, but to seek to raise awareness and push for meaningful changes in whatever ways we can. This can be in the form of public resolutions by various groups and denominations bringing awareness to these atrocities, such as the recent resolution against the Uyghur Muslim genocide in China from the Southern Baptist Convention, or by even advocating for various government measures, such as the recent genocide designation by the U.S. government for the atrocities being committed by the CCP.14

These declarations against the exploitation and unjust treatment of our fellow human beings can help send a powerful signal to authoritarian regimes everywhere that the world will not sit idly by as they subjugate their citizens under the pretext of preserving national security or unity. And as more than 80 evangelical leaders said recently in a joint statement: “We must condemn the use of any (technology) to suppress free expression or other basic human rights granted by God to all human beings.”15 Technology is a powerful tool that can easily be used by those who seek power and prestige over justice and righteousness. While many of these tools used in digital authoritarianism may be cutting edge and innovative, there is nothing new about the dehumanizing effects of authoritarianism. Christians must call out these injustices wherever they are found and proclaim to the world that people created in God’s image are not disposable nor are they a means to unchecked power.

1 Andrea Kendall-Taylor, Natasha Lindstaedt, and Erica Frantz, Democracies and Authoritarian Regimes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 294.

2 Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1964), p. 229.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid., p. 247.

5 Ibid.

6 “China: ‘The World’s Biggest Camera Surveillance Network,’ ” BBC News, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pNf4-d6fDoY, accessed May 4, 2020.

7 Roland Hughes, “China’s Muslim ‘Crackdown’ Explained,” BBC News, November 8, 2018, sec. China, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-45474279.

8 Elizabeth Economy, The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 59.

9 Ibid., pp. 58, 59.

10 “Belarus Has Shut Down the Internet Amid a Controversial Election | WIRED,” https://www.wired.com/story/belarus-internet-outage-election/, accessed June 21, 2021.

11 Jason Thacker, “Explainer: Iran, Fuel Costs, and the Internet Shutdown,” ERLC, November 21, 2019, https://erlc.com/resource-library/articles/explainer-iran-fuel-costs-and-the-internet-shutdown.

12 Kendall-Taylor, Lindstaedt, and Frantz, p. 295.

13 Alan Jacobs, “No Time but the Present,” Harper’s Magazine, September 10, 2020, https://harpers.org/archive/2020/10/no-time-but-the-present-breaking-bread-with-the-dead-alan-jacobs/.

14 Chelsea Patterson Sobolik, “U.S. Announces Genocide Determination for the Ongoing Atrocities Committed against Uyghurs,” ERLC.com, January 19, 2021, https://erlc.com/resource-library/articles/u-s-announces-genocide-determination-for-the-ongoing-attrocities-committed-against-uyghurs/.

15 “Artificial Intelligence: An Evangelical Statement of Principles,” April 11, 2019, https://erlc.com/resource-library/statements/artificial-intelligence-an-evangelical-statement-of-principles.

Article Author: Jason Thacker

Jason Thacker serves as assistant professor of philosophy and ethics at Boyce College and a senior fellow in Christian ethics at The Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. He is the author of several books, including Following Jesus in a Digital Age and The Digital Public Square: Christian Ethics in a Technological Society.