WWJD?

Lincoln E. Steed November/December 2005

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

I know that many Christians were startled recently to hear televangelist Pat Robertson call for the elimination/assassination of President Chavez of Venezuela. Astute political observers know that such an idea is not exactly off the table: indeed; it was a failed U.S.-backed coup against Chavez that fed his paranoia. But official U.S. policy forbids such an action. And what about the "gospel of peace"—the Christian imperative to respect life? One would have to look to the mind-set of "Christians" such as Torquemada the Inquisitor to find a rationale to justify calling for the death of another human.

Are we dangerously desensitized to the morality, or lack of it, in language? There is a modern irony in the fact that with the proliferation of acronyms the meaning behind them is often diminished. WMD is a case in point—overuse of the term has trivialized this invocation of unimaginable destruction to a sort of "Where's Waldo?" game for Senate hearings.

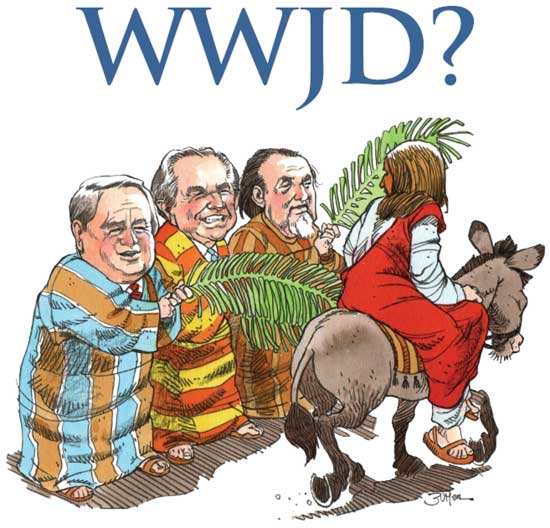

And then there's WWJD. An election cycle or two ago Americans at large got to learn about the WWJD acronym—which stands for What Would Jesus Do? I'm afraid it began the trivialization of a necessary internal process that all true Christians follow in living out their faith. Perhaps it is telling that some are more concerned about posting a set of religious regulations in public places than in honoring the spirit of Jesus Christ Himself—both the Creator and a model for human behavior.

Jesus came at a time when the religion of the true God was restricted by an oppressive secular power. He ministered to a people with religious aspirations. He never deviated from His call to join the kingdom of God. He never confused that kingdom with the secular one. He never sought secular power.

At the conclusion of His earthly ministry Jesus quite consciously staged a triumphal entry into Jerusalem. He entered the city seated on a colt—a traditional sign of kingship. And the crowd honored Him in the manner that they would a king assuming power.

Many who waved palm fronds along the way assumed that He was coming into secular power. Many of the simple people who had seen the miracles imagined that He was about to perform a political miracle. Indeed, some of His own disciples, notably Judas, were led by the same expectation.

They should have understood the transcendent nature of that coming to power. They should have listened to Jesus speak sadly of the great city rejecting the prophets. They should have paid attention to His warning of the collapse of their secular hopes in the destruction of Jerusalem. They should have noted that even at this moment of triumphal entry, Jesus was directed toward reforming the behavior of those at the Temple—as He cleansed it of commerce.

Only later did they note that Jesus told Pilate "My kingdom is not of this world. If My kingdom were of this world, My servants would fight" (John 18:36).

So what would Jesus do in America today?

I think many Christians and others of faith would expect Him to weep over the moral state of affairs. It is proper for someone who has learned of the Christ to anguish over the troubles of society.

It would seem obvious that were He among us today, Christ would still be calling for inner renewal and a commitment to the kingdom of heaven.

And if He were here today, by what logic could we expect Him to seek political power to advance a Christian agenda? The Bible record and the life of Christ are all too clear on this. "My kingdom is not of this world." And to Peter He said, "Put your sword in its place, for all who take the sword will perish by the sword" (Matthew 26:52).

I believe that many of my fellow Christians in the United States are in danger of reaching for the sword to solve a spiritual problem. And while the misstatement of Pat Robertson has been apologized for, it does stand as a sort of Freudian slip concerning a larger tendency that has overtaken many of the politically active Christian groups, which have grown in number and following way beyond the Moral Majority movement begun by Pat's fellow televangelist Jerry Falwell.

So often in putting this magazine together and in discussing the issues with others, we use the term the religious right, and usually criticize what the group is doing on church-state issues. This is unfortunate for several reasons.

First: there is no truly monolithic religious right. There is an array of groups and issues they wish to address. What we are trying to identify and address is the now patently self-evident general tendency of some groups to seek solutions through gaining political power. And in the process they have become dismissive of the constitutional construct of a separation of church and state. And forgetful of the similar call from our Lord Jesus.

Second: while these politically active groups have come to pose a very real threat to true religious freedom, I recognize that most of their specific concerns are ones I share. Issues of public immorality, abortion, euthanasia, and family breakdown concern me. But I must recognize that the most effective way to counter these is by public witness and a change in spiritual values.

Third: critiquing the movement composed of these groups can imply that we are blind to the very real threat to faith posed by radical secularists. We cannot afford to ignore this, of course. But the reason Liberty speaks more often to the issue of right wing religious fundamentalism is precisely that, good intentions aside, it does pose a far greater constitutional threat to religious liberty. Radical secularists are attempting to use the Constitution to minimize or remove religion from public life. But they have no power over religion itself. However, many in the politically active religious right are dismissive of the First Amendment; want government funding of religion (something the Framers discussed and rejected); seem intent on gaining power through extraordinary means; and have confused the historic Christian cast to American society with their plan to support a "Christian America" by government patronage.

What would Jesus do? must become an inner compass for all of us who claim to follow Him. Jesus was a revolutionary precisely because He took the battle for change into the inner, spiritual dimension. There were plenty of Zealots in His day ready to take on the political structure. Jesus was not of their party. He spoke about power on occasion. In fact, His comment about Herod was amazingly direct. But when He met Herod, there were no miracles for the secular "fox" (see Luke 13:32).

Shortly before the American Revolution there was a broad-based revival of religion in the Colonies. From the 1730s through the 1770s the Great Awakening stirred the populace. It became a dynamic for change under the exhortation of religious luminaries such as Jonathan Edwards and visiting superstar George Whitefield. That such a society could knowingly frame a Constitution that kept faith and political power in their proper spheres is admirable and evidence that the religious revival was a true one.

So often I have heard religious conservatives pray the prayer that God will "heal our country." In the post-Katrina shock many yearn for that healing. If more of us pray that way and apply it in our lives the true WWJD way, I believe that powerful things will happen in America.

Lincoln E. Steed

Editor,

Liberty Magazine

Article Author: Lincoln E. Steed

Lincoln E. Steed is the editor of Liberty magazine, a 200,000 circulation religious liberty journal which is distributed to political leaders, judiciary, lawyers and other thought leaders in North America. He is additionally the host of the weekly 3ABN television show "The Liberty Insider," and the radio program "Lifequest Liberty."